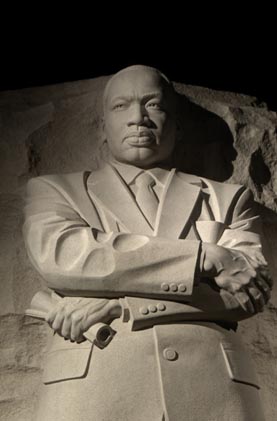

(photo by Scott Ableman)

DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.’S BIRTHDAY (BELOVED COMMUNITY DAY)

LECTIONARY COMMENTARY

Sunday January 20, 2013

Robert S. Harvey, Guest Lectionary Commentator

Director of Student Life, The Fay School

Lection – Matthew 5:43-45 (New Revised Standard Version)

(v. 43) ”You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ (v. 44) But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, (v. 45) so that you may be children of your Father in heaven.”

I. Description of the Liturgical Moment

For African American Christian communities around the country, the life and teachings of Martin Luther King Jr. represent a human archetype of the radical gospel of love. Considered the formative figure in the modern fight for civil rights, King’s prophetic voice as a democratic revolutionary was a voice that reverberated with the sacred call of “liberty and justice for all.” At the core of his message was his belief in the creation of the beloved, a community of all human persons committed to an ethic of love—an infinitely redemptive love, inclusive of friend and foe. On Beloved Community Day, millions of Christians from every walk of life and corner of the world pause to celebrate a love ethic grounded in the gospel of Jesus. Throughout the gospel narratives, Jesus prophetically trumpets that access to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” is found in a new commandment, “love one another: just as I have loved you, you also should love one another” (John 13:34). On this day where we pause to celebrate and honor the beloved community, we should be found returning to the church’s first love—the social, compassionate, and loving gospel of Jesus the Christ.

II. Biblical Interpretation for Preaching and Worship: Matthew 5:43-45

Part One: The Contemporary Contexts of the Interpreter

As I pause in the midst of daily realities to reflect and meditate on the cultural, theological, and political importance of creating a beloved community, my mind turns to a sermonic elocution by Reverend Mary McKinnon Ganz. In the introduction to her sermon, “Building Beloved Community,” Ganz relates Jesus’ emphasis on the “kingdom of God” and King’s accent on the beloved community with the Buddhist tenet of “dependent arising.” “In the words of Jesus, King, and Buddhist teachings we learn that my actions affect every one of you, and your actions, affected by my actions and by the actions of all you are in relationship with, affect me and countless others, who affect countless others. Nothing that happens, happens on its own; it all happens in the context of and at the effect of all that is.”1 What Ganz highlights is that this eschatological dream of a community where the hearts, minds, and hands of all are dignified, and the content of humanity surpasses the characteristics of difference, is a dream shared by the prophetic minds of many traditions. Biblically, the beloved community is a twentieth-century articulation of the “kingdom of God,” a kingdom spoken of by Jesus where all persons are invited to sit at the table, drink from a flowing well, and bask in the peace of a loving God.

As we co-create a beloved community in a world where militaristic terrorism, depressing markets, and racial, gender, and orientation injustice persist, the observance of Beloved Community Sunday must consistently hold together the belief that our characteristic differences are the underpinning of our beloved community. If it persuades us in any way, Beloved Community Sunday must both honor the prophetic declarations of a dreamer commingled with actions that move our society forward to a place where we can honor those persons who are unjustifiably denied their dignity as citizens of the inclusively loving “kingdom of God.”

Part Two: Biblical Commentary

This Gospel pericope unfolds in the context of Jesus’ sermon on the mount, delivered on a mountain near Capernaum. This scene cannot be located in any of the other Gospel narratives, with the closest equivalent being Jesus’ sermon on the plain in the writing of Luke. Theologians agree that as Jesus offered his sermonic corpus, he took the posture of sitting, a rabbinical tradition, which denotes authority. In fact, it is postulated that the writing of Matthew presents Jesus as a new Moses, aimed at addressing the socio-cultural and theological needs of a particular early community, located at Antioch in Syria, which included many seekers of Jesus’ relationship with God. The fulcrum of this particular text is the reformation of Hebraic thought with regards to Jewish regulations of the love ethic. In Matthew, unlike the other three Gospels, the writer is particularly preoccupied with pharisaic observances and scribal interpretations of the Mosaic law as we note in reading our text.

Pope Benedict XVI accordingly observes, “The Sermon on the Mount is the new Torah brought by Jesus, as the new Moses whose words constitute the definitive Torah.” In addition, many Judeo-Christian thinkers assert that this sermon as started in chapter 5 can also be understood as the beginning of a new covenant which God was establishing with the new Israel as the opening address of Jesus inaugurating the “kingdom of God,” the beloved community. From what we have seen in the movement of the sermon, our particular text is intended to identify the way in which the followers of Jesus should behave in loving all of God’s created humanity—a thought and practice grounded in the creation of a beloved community.

The Misinterpretation of Love

At the onset of our text, Jesus is responding to the Hebraic understanding of the Law, which instructed persons to “love your neighbor as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18). Imbedded in Israel’s understanding of this teaching are two fatal mistakes in interpretation, both of which have continued to inform human thought and more importantly, social behavior until this day. The first misinterpretation is the belief that the title of “neighbor” only applied to those persons who were situated in their own community, religion, and nation; the word “neighbor” was used in exclusion to “the other” and was reservedly applied to those who identified as Israel identified. In point of fact, Israel both literally (and theologically) degraded interactions with any human person identified as “the other” because the second misinterpretation was the inference that loving their neighbors (who were like them) meant to hate their enemies (who were “the other”).

Otherness, theoretically, is the process by which dominant individuals, cultures, societies, groups, institutions, and social frameworks exclude ‘others,’ whom are deemed by the dominate group to be subordinate and inappropriately fitted elements of the dominant society. In this context, otherness is rooted in and defined by “difference,” and typically that difference is marked by biological and involuntary elements, for example, race, sex, or ethnicity. Otherness is a behavioral quality by which we distinguish the familiar and the unfamiliar, subconsciously stratifying and leveling individuals, groups, and cultures, which further justifies attempts to oppress those unlike us. It is in this context that we begin to see what Jesus is addressing when opens with the words, “You have heard that it was said…” In other words, Jesus is acknowledging that the Hebrew people have been cultivated (by an act of theological socialization) to adopt the rejection of otherness, and conversely the acceptance of samenessas the paradigm for love.

In Hebrew thought, if God said to “love your neighbor,” they reasoned and added that the subsequent directive was to “hate your enemy.” Unfortunately, this thought of “hate your enemy” was the dominant thought that guided all Jewish social participation. This inference that the opposite of “love your neighbor” was hatred for those who were non-Jewish can be located in the words written in the Mishnah: “A Jew sees a Gentile fall into the sea, let him by no means lift him out; for it is written, Thou shalt not rise up against the blood of thy neighbor: but this is not thy neighbor” (Mishnah Torah, Laws of Murder 4:11). This arrant misinterpretation of the love ethic situated in the beloved community is a delusion that has continued to inform humanity, particularly within our religious commitments—in thought and practice. Many of us who identify as Christians, attempting to Christ-centered and gospel-informed lives, fall into the same misinterpretation as Israel by inferring our “neighbors” to only be friends, family members, people who live within relative closeness, persons who think like we do, and a selective set of church attendees. We often do not reason that our enemies or the citizens of the world as a whole are our neighbors and thus possess the inherent human dignity to receive our love.

Thousands of years later, Jesus’ words, (v. 43) “You have heard that it was said…” lamentably continue to speak truth to our cultural and theological misinterpretation of love. The dominant misconceived logic of our humanity, which King critiqued with his twentieth-century articulation of the “beloved community,” is the rampant xenophobia (‘fear of the other’), which has infected our theology, our politics, and our culture. The “beloved community”—a community grounded in the dignity of all human persons—cannot occur with the predominating ‘fear of the other’: it can only exist as a result of a theology and a culture that proffers an invitation of love to all people.

The Motive of Love

At the heart of our pericope, as it is at the heart of the beloved community, is the transformative faculty of unyielding, unpretentious, and unbounded love—agape. Our New Testament writings are laced with this idea of self-giving love, particularly those attributed to John, sometimes known as Jesus’ “beloved” disciple, and Paul, a key messenger to and builder of early communities of Jesus’ followers. King described agape love as “understanding, redeeming goodwill for all men. It is an overflowing love, which is purely spontaneous, unmotivated, groundless and creative. It is the love of God operating in the human heart. Agape does not begin by discriminating between worthy and unworthy people. It begins by loving others for their [own] sake”2 and in turn, makes no distinction between friend and enemy; it is a directed love toward both with equality. In essence, agape is selfless love that seeks to create, safeguard, and advance community.

The writer of this Gospel narrative chose to use “agape” because the motive of the love we have been called to is a love not dependent on being loved back—it is a selfless and radical love, which is inclusive of all persons, regardless of being included in return. Within post-modern lived experience, there is often a self-centeredness that pervades in what we call “love”—a love that is only distributed as we are able to identify what we “get out of it.” The potency of Jesus’ instruction of “agape” is that it was a call for humanity to love indiscriminately, which implies a love that is both universally accessible and impartial and humble. To those listening to Jesus in his age and even to those who continue to listen to his words today, this ethic of selfless, radical, transformative, creative, and redeeming love is a radical migration from the Old Testament ethic of an “eye for an eye” and often appears like an impossibility. This ethic of a love is one that places the ultimate good of another person above the good of one’s self, which even goes beyond the classically articulated, ‘Golden Rule,’ which tells us to treat others only as equal to ourselves.

The point of Jesus’ words in Matthew 5:44-45 is to challenge the conventional wisdom of verse 43—”to love your neighbor and hate your enemy”—and ultimately inspire us to take our theological cues of love not from the Levitical inference and misinterpretation to “hate your enemy” but to replicate the motives of God. Jesus informs those listening, and thereby informs us today, to realize that our capacity to be called children of God is in our capacity to show creative and redeeming love to all persons, just as God shows his creative and redeeming love to each of us.

Behind King’s conception of the beloved community and Jesus’ assertion to “love your enemies and pray those who persecute you” in verses 44 and 45 is the idea that we as a humanity “are tied together in the single garment of, caught in an inescapable network of mutuality.”3 This was a way of affirming that reality is made up of structures that form an interrelated whole; in other words, that human beings are dependent upon each other. Whatever a person is or possesses he owes to others who have preceded him. As King wrote: “Whether we realize it or not, each of us lives eternally ‘in the red.’ Recognition of one’s indebtedness to past generations should inhibit the sense of self-sufficiency and promote awareness that personal growth cannot take place apart from meaningful relationships with other persons, that the ‘I’ cannot attain fulfillment without the ‘Thou.’”4

One of the leading thinkers of love’s motive as a force which connects and unites all humanity and God is Paul Tillich. In his seminal work, Love, Power, and Justice, Tillich sets out his description of love, beginning with the interconnected relationship between love and life: “Life is being in actuality and love is the moving power of life.”5 In other words, when a human being ceases to be merely possible, and becomes an actual, Tillich proffers that we can say it is “alive”; and the very power (or force), which moves beings from possible to actual—the thing which moves beings into life and through life—is called “love.”

For Tillich, as well as for Jesus according to our text in verse 45, this means that being requires love as a force in order to become an “actual.” Furthermore, as we reconstruct the Hebraic misinterpretation of “love your neighbor and hate your enemy,” it is only through love that we learn what the totality of life really is, to be called “children of God.” Tillich narrows his description of love as a force when he writes: “Love is the drive towards the unity of the separated. Reunion presupposes separation of that which belongs essentially together.”6 In other words, the very motive of love both between humans with humans and between humanity with God is to unite those beings, which are inherently one. As we believe that all of us “are made in the image of God, and in his likeness” (Genesis 1:27) the love we are called to demonstrate toward our enemies cannot be described as the union of the strange but as the reunion of the estranged. Since estrangement presupposes original oneness, all of us in the human family are one—neighbor and neighbor, neighbor and enemy, enemy and enemy, and all with God. Our basis as a people is oneness, and our basis with God is oneness, and thus the love-force that gives life meaning is a love that reunites all of us back to each other and back to God in beloved community.

Dr. King, like Tillich, understands the motive of love as a force, which drives our lives to an altar of reconciliation. Speaking to a conclave of clergy and laity at Riverside Church, King opined: “When I speak of love I am not speaking of some sentimental and weak response. I am speaking of that force which all of the great religions have seen as the supreme unifying principle of life. Love is somehow the key that unlocks the door, which leads to the ultimate reality.”7 Jesus affirms this motive of love as a force that gives life in verse 44 when he submits to “Love your enemies.” By offering us a subject—our enemies—as qualified by a verb—love—we begin to see his theological reconstruction of the Hebrew misinterpretation of love as a reserved action for those who are our “neighbors.” Jesus is addressing how we are called as “children of God” to turn to love, always, regardless of how our neighbors, enemies, and persecutors treat us. Instead of weltering in the misinterpreted tenet of “hate your enemies,” we must grasp that ultimate reality in our lives is solely unearthed in love. Creating a beloved community of love and reconciliation, where friend and foe share a place at the same table of God, makes it imperative that we abscond the misinterpreted beliefs in life: hurt those who hurt you, despise those who despise you, or reject those who reject you. Creating a beloved community, a community with one table where all are welcome, makes it imperative that we adopt a belief that just as God “makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good” we too must allow our love to rise on the evil and on the good. The word “rise,” located in verse 45, is the Greek word anatellei—a verb which denotes “he causes and (makes to happen) a rising.” In essence, when Jesus articulates that God “makes his sun rise,” he is articulating that God is an active and participatory function of the sun rising “on the evil and the good.” Thus, as we are the children of God, the love we have been called to demonstrate is a love that necessitates that we are active and participatory.

Celebration

We celebrate the expansive love and guarantees of our faithful God who shines his compassionate light on the evil and the good. We can worship because we have a God who is concerned about bringing what King called “the disjointed elements of reality” into a harmonious whole. We can worship because we have a God who, in and through Jesus, is about reconciling people to himself, reconciling people to themselves, and reconciling people to each other. Though disunity and discord seem so natural to the human spirit, there is a calling for those who proclaim the gospel of reconciliation to work toward the beloved community. The church, when it is most authentic, is a symbol of the beloved community. As the Church, we forge bonds between people beyond the experience of worship to the larger realms of society and the world. We worship because creating the “beloved community” successively creates a visual image of love “to represent the heart of the Christian message: a group of human beings of varying races, ethnicities, nationalities, genders, physical abilities and disabilities, and economic classes.”8 We celebrate because Jesus underscores a creative, transformative, and redeeming love of radical inclusivity that invites, welcome, and sustains all who may come!

Descriptive Details

The descriptive details of this passage include:

Sounds: The voice of Jesus;

Sights: Jesus sitting; attentive listeners; enlightened faces; and perplexed dispositions.

III. Other Sermonic Comments or Suggestions

Congregational Prayer

God of Community, Love, and Reconciliation!

We come before you on this divine day with unabridged submission, undivided gratitude, and unconstrained joy because your love knows no bounds. We come before you, God, because no hindrances or obstacles—including those we have created—can impede your creative, transformative, and redeeming love from accompanying us on all sides as we walk through the valley of the shadow of death. On this day, we pause to celebrate a prophetic leader and work toward the creation of his social prophecy—a beloved community—a community of love and hope and compassion for our neighbors. We praise and worship you for altering our understanding of whom we must love; we recognize that our neighbors are not only those persons who believe like us, practice like us, and confess like us, but our neighbors are all persons within the human family. God, we welcome you unconditionally, which is in the manner that you welcome us. We present ourselves before you—broken, hurt, and even shattered—seeking to be reconciled forever to the loving embrace of your holiness, your wonder, and your kingdom. As we participate with you in co-creating a beloved community, fortify us with the confidence of your presence and your peace. In your name, with the community of the human family, we do pray. Amen.

Quotation(s)

The question should not be “What would Jesus do?” but rather, more dangerously, “What would Jesus have me do?” The onus is not on Jesus but on us, for Jesus did not come to ask semidivine human beings to do impossible things. He came to ask human beings to live up to their full humanity; he wants us to live in the full implication of our human gifts, and that is far more demanding.

| |

—Peter J. Gomes, The Scandalous Gospel of Jesus, 2007

|

Although man’s moral pilgrimage may never reach a destination point on earth, his never-ceasing strivings may bring him ever closer to the city of righteousness. And though the Kingdom of God may remain not yet a universal reality in history, in the present it may exist in such isolated forms as in judgment, in personal devotion, and in some group life. Above all, we must be reminded anew that God is at work in his universe. As we struggle to defeat the forces of evil, the God of the universe struggles with us. Evil dies on the seashore, not merely because of man’s endless struggle against it, but because of God’s power to defeat it.

| |

—Martin Luther King, Jr., Struggle to Love, 1961

|

The aftermath of non-violence is the creation of the beloved community; the aftermath of non-violence is redemption and reconciliation. This is a method that seeks to transform and to redeem, and win the friendship of the opponent, and make it possible for men to live together as brothers in a community, and not continually live with bitterness and friction.

| |

—Martin Luther King, Jr., “Justice without Violence,”

Brandeis University, 1957 |

Love is creative and redemptive. Love builds up and unites; hate tears down and destroys. The aftermath of the ‘fight with fire’ method, which you suggest is bitterness and chaos, the aftermath of the love method, is reconciliation and creation of the beloved community. Physical force can repress, restrain, coerce, destroy, but it cannot create and organize anything permanent; only love can do that. Yes, love—which means understanding, creative, redemptive goodwill, even for one’s enemies—is the solution to the race problem.

| |

—Martin Luther King, Jr., 1957 |

Congregational Songs

In January 2012, as Reverend C. T. Vivian recalled the spiritual life of his friend and colleague, Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., he reminisced on hymns that touched his friend. As a group of civil rights clergy concluded a meeting in King’s home, Reverend Vivian recalled the Negro spiritual “There Is a Balm in Gilead” being started, and upon hearing the first stanza Dr. King with “his eyes closed, rocking back and forth on his feet,”9 was comforted by the words of that hymn. Below is a list of hymns, as articulated by Reverend Vivian, that inspired and comforted Dr. King:

- There Is a Balm in Gilead. Negro Spiritual

- Precious Lord, Take My Hand. By Thomas A. Dorsey

- How I Got Over. Traditional spiritual

Book Recommendations

|

Peter J. Gomes. The Scandalous Gospel of Jesus: What’s So Good about the Good News? New York, NY: HarperCollins, 2007. |

|

|

|

Charles Marsh. The Beloved Community: How Faith Shapes Social Justice from the Civil Rights Movement to Today. New York, NY: Basic Books, 2005. |

|

|

|

Phillip Gulley and James Mulholland. If God Is Love: Rediscovering Grace in an Ungracious World. New York, NY: HarperCollins, 2004. |

|

Josiah Royce. The Problem of Christianity. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2001. |

|

Kenneth L. Smith and Ira G. Zepp, Jr. Search for the Beloved Community: The Thinking of Martin Luther King. Jr. Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press, 1974. |

Notes

1. Mary McKinnon Ganz. “Building Beloved Community,” a sermon given at First Parish Brewster, Brewster, Massachusetts, on January 15, 2012.

2. Martin Luther King, Jr. A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr. New York, NY: HarperOne, 1990.

3. Martin Luther King, Jr., “Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution,” an address given at Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio, in June 1965.

4. Kenneth L. Smith and Ira G. Zepp, Jr. “Martin Luther King’s Vision of the Beloved Community.” Christian Century (1974): 362.

5. Paul Tillich. Love, Power, and Justice. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1954, p. 25.

6. Ibid.

7. Martin Luther King, Jr. “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence,” a lecture given at Riverside Church, New York City, on April 4, 1967.

8. Barbara Darling. “A New Symbol for Christianity,” Tikkun, October 26, 2012. Online location: http://www.tikkun.org/nextgen/a-new-symbol-for-christianity accessed 1 November 2012.

9. Adelle M. Banks. “Hymns Comforted Martin Luther King,” The Kansas City Star, January 13, 2012. Online location:

http://www.kansascity.com/2012/01/13/3368546/hymns-comforted-martin-luther.html accessed 11 October 2012.

|