“Rain or Shine: Washington, D.C. Elderly couple eating dinner at their home on Lamont Street, N.W.” Photo by Gordon Parks. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection [LC-USF34-013404-C].

|

MARRIAGE ENRICHMENT SUNDAY

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Sunday, March 25, 2012

Donyelle McCray, Guest Cultural Resource Commentator

Doctor of Theology Candidate, Duke Divinity School, Durham, NC

I. Introduction

I’ve found that truths about marriage can be hard to come by. That’s why I am grateful to award-winning photographer Gordon Parks who took the photo that is our main image for today in June of 1942. It would be so easy to show us a couple of newlyweds grinning behind a wedding cake or a pair of spry seniors peering triumphantly over a 50th anniversary cake. But Parks is telling a different story about a couple grayed and bent by time and matrimony. They are pictured here in the midst of their daily routine, quietly meeting the requirements of everyday life.

Everyday life has brought unique challenges to African American marriages. In addition to the typical bag of misunderstandings, frustrations, and quirks that every couple faces, African American couples also press against the intertwined powers of racism, sexism, class discrimination, and homophobia. Whether we discern a call to marriage or to one of the many varieties of singleness, we can learn a lot from our married ancestors. Their stories of sorrow and triumph can guide us as we build the kind of loving relationships that can sweeten our everyday lives.

II. Songs of the Moment

Marital bonds have a sacred quality in African American life for reasons more fundamental than religious belief. Romantic space is one of the few places with the potential to honor our full humanity. We even have the freedom to be playful, as illustrated in this chorus made famous by funk-master extraordinaire, Little Milton:

If I don’t love you baby,

Grits ain’t grocery,

Eggs ain’t poultry,

And Mona Lisa was a man.

Delightful as it is, Little Milton’s playfulness does not tell the whole story. Bluer notes have played a critical role in African American marriages as partners have had to do the hard work of naming their losses, exposing their emotional wounds, and inching their way toward deeper levels of trust. B.B. King does an especially good job of exposing emotional wounds in his blues song “Nobody Loves Me but My Mother.” His raw honesty about feeling unloved is both comic and tragic, and he shows just how much is at stake in the relationship. B.B. King describes a relationship which, like many African American marriages, is weighted down by the past and unclear (though still hopeful) about the future.

Nobody loves me but my mother

And she could be jivin’ too

Nobody loves me but my mother

And she could be jivin’ too

Now you see why I act so funny, baby

When you do the things you do

What I wanna know now

Is what we gonna do?

The “response” to B.B. King’s plea can be found in a classic song written by Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer, “Come Rain or Come Shine.” A host of great performing artists have performed versions of the song, including Billie Holliday, Sarah Vaughn, Dinah Washington, Ray Charles, Ella Fitzgerald, Dianne Reeves, and Natalie Cole. Each of these performers has captured the passion in the lyrics and sang of a fearless love that will not shy away in the face of life’s inevitable ups and downs.

I’m gonna love you like nobody’s loved you come rain or come shine

High as a mountain and deep as a river come rain or come shine

I guess when you met me it was just one of those things

But don’t ever bet me cause I’m gonna be true if you let me

You’re gonna love me like nobody’s loved me come rain or come shine

Happy together unhappy together and won’t it be fine?

Days may be cloudy or sunny

We’re in or we’re out of the money

But I’m with you always, I’m with you rain or shine

I’m gonna love you like nobody’s loved you come rain or come shine

High as a mountain deep as a river come rain or come shine

I guess when you met me it was just one of those things

But don’t ever bet me cause I’m gonna be true if you let me

You’re gonna love me like nobody’s loved me come rain or come shine

Happy together unhappy together and won’t it be fine?

Days may be cloudy or sunny

We’re in or we’re out of the money

But I’ll love you always, I’m with you rain or shine

Rain or shine.

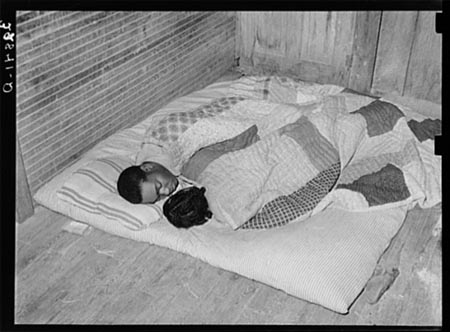

“Negro couple, intrastate migratory workers, sleeping on the floor. Near Independence, Louisiana,” April 1939. Photo by Russell Lee. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection [LC-USF34- 032841-D].

|

III. Historical Notes on African American Marriage

Some of the first historical records of African American marriage appear during the 1860s. Prior to this time couples ritualized their marital commitments by jumping the broom or exchanging promises. Legally documented African American marriages do not appear in the South on any large scale until the Civil War when Union Army chaplains began to preside over marriages between Black recruits and their brides. In these ceremonies many couples enjoyed a new-found level of freedom. Their most intimate relationships were no longer subject to the convenience of a slave master and their verbal promises were respected by the state for the first time. They could also claim their own identities by choosing a name or taking on the spouse’s surname instead of the master’s.1

While legal marriage represented a step forward, the heartfelt commitment in slave marriages should not be underestimated. Tempie Herndon Durham married Exter Durham when both were serving as slaves on different North Carolina plantations. Exter made a wedding band for Tempie out of a large red button, smoothing the inside of it with his pocket knife until he was sure she could wear it comfortably. “I wore it ‘bout fifty years,” Tempie said, reflecting on her wedding band. In fact, she wore it until it got so thin that she lost it washing clothes.2 By the time legal marriage was an option for them, Tempie and Exter had nine children and Tempie was especially grateful for the two children who were born free.

After emancipation, many Black couples married through the Freedmen’s Bureau. Often these ceremonies involved couples who, like Tempie and Exter, had already been together for years and finally had the opportunity to make their commitments legal. It is important to note that slaves coupled in a variety of patterns, including but not limited to lifelong commitments. The turn to marriage and state regulation offered both direly-needed protections as well as the constraints of genteel respectability.3 Thus, marriage was not an entirely free process; to some extent it required assimilating to the marital patterns of the white establishment.

In any event, marriage did not guarantee an easy path. Couples faced challenges that might give us pause today. Basic survival presented its own challenges, but in addition the threat of violence during Reconstruction was particularly ominous. In fact, Kerry Segrave documents 19 African American couples who are lynched during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.4 Usually when we think of lynching we think of male suffering—not a husband and wife dangling together. Yet, Segrave begins by recounting the case of Mr. and Mrs. Matt Nickles and Mr. and Mrs. Henry Reed. Both couples were lynched in October of 1869 in Jackson County, Florida, as armed mobs ran rampant through the community.

|

|

|

|

|

|

It’s hard to find language to describe this kind of horror, and space does not allow a full examination of the implications here. This history does, however, urge us to ask serious questions: Were events like these on the minds of our ancestors when they said “until death do us part”? Does this history give us a deeper sense of what Black love has had to endure? Does it color Paul’s teaching in 1 Corinthians 13 of a love that “endures all things”? Better yet, can this legacy inform our commitments today? Can it stir our commitment to justice and nonviolence—especially in intimate relationships? Can it inspire genuine tenderness?

Coupling is an effort in tenderness; it’s a celebration of personhood in a society that systematically denies full humanity to people of color. I would even say that the devoted Black couple, coming together out of a sense of choice rather than compulsion, is a political unit—a challenge to the social order. Our affective relationships are in themselves a form of resistance to oppression. And the power of this resistance increases even more when couples are not just islands in themselves but deeply committed to others such as extended families or intentional Christian communities. Couples become signs of life—genuine gifts of hope to the world.

“Negro couple at grave of relative, All Saints' Day in Cemetery at New Roads, Louisiana,” November 1938. Photo by Russell Lee. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection [LC-USF3301-011887-M3].

|

IV. Visual Resources & Display Ideas

A number of images may enhance listeners’ experience of a sermon on marriage enrichment. Instead of images of wedding cakes or brides and grooms, opt for images that emphasize a relationship’s strength and longevity. These might include:

- Silhouettes of couples;

- Wedding bands;

- Images of handwritten letters, ink or pencil;

- An image of a marriage certificate, especially from the antebellum era, though a marriage certificate issued as late as the 1950s may be equally inspiring. The following link to the National Archives provides images of marriage certificates for John and Emily Pointer, who were married at the Freedmen’s Bureau in 1866, and Benjamin and Sarah Manson, who were married at the Freedmen’s Bureau in 1867. Prior to the formal ceremony at the Freedmen’s Bureau, Benjamin and Sarah had been together for more than twenty years. Follow this link to see marriage certificates:

http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2005/spring/freedman-marriage-recs.html

V. Love Letters

With the advent of e-mail, handwritten love letters have become increasingly rare. Whether penned on aging parchment or delicately folded stationery, letters between spouses provide some of the most powerful portraits of African American marriage. Some letters travel dangerous territory and reveal great risk. Others describe a playful tenderness and longing for reunification. Consider the following letter from John Boston to his wife Elizabeth, written in 1862. John had just escaped from slavery and writes to her from New York. While he is dazzled by the joys of freedom, we can also sense that he misses his wife terribly.

| |

Upton Hill [Va.] January the 12 1862 |

My Dear Wife

it is with grate joy I take this time to let you know Whare I am. i am now in Safety in the 14th Regiment of Brooklyn this Day i can Adress you thank god as a free man I had a little truble in giting away But as the lord led the Children of Isrel to the land of Canon So he led me to a land Whare fredom Will rain in spite Of earth and hell Dear you must make your Self content i am free from al the Slavers Lash and as you have chose the Wise plan Of Serving the lord i hope you Will pray Much and i Will try by the help of god To Serv him With all my hart I am With a very nice man and have All that hart Can Wish But My Dear I Cant express my grate desire that i Have to See you i trust the time Will Come When We Shal meet again And if We dont met on earth We Will Meet in heven Whare Jesas ranes Dear Elizabeth tell Mrs Own[ees] That i trust that She Will Continue Her kindness to you and that god Will Bless her on earth and Save her In grate eternity My Acomplements To Mrs Owens and her Children may They Prosper through life I never Shall forgit her kindness to me Dear Wife i must Close rest yourself Contented i am free i Want you to rite To me Soon as you Can Without Delay Direct your letter to the 14th Reigment New york State malitia Uptons Hill Virginea In Care of Mr Cranford Comary Write my Dear Soon As you C Your Affectionate Husban Kiss Daniel For me

John Boston

Give my love to Father and Mother

Historians do not know whether Elizabeth ever actually received John’s note. The Maryland House of Delegates eventually obtained the letter and tried to use it to capture John Boston and other fugitive slaves like him.5

Other couples experience a greater sense of freedom but an equally strong attachment. Dr. Charles Drew is best known for his pioneering work as a medical researcher and creator of the modern blood bank. Yet in his relationship with his beloved wife, Lenore Robbins Drew, the doctor-patient roles were reversed. He became a lovesick patient and his wife held the cure.

| |

Sunday Afternoon

[undated ca. 1940]

|

Darn it all Lenore,

I’m supposed to be here [Columbia University-College of Physicians and Surgeons] working, but work is the farthest thing from my mind. I’m simply no good at it. It’s terribly disturbing, disorganizing, inefficient, demoralizing, upsetting, frustrating, understandable—delightful. The sap has gone crazy, grins at himself, preens, struts, blushes, smiles, laughs, whistles, sings and then just sits in a daze. Got heartburn, palpitation, indigestion, anorexia, psychasthenia, euphoria and delusions of grandeur. Hallucinations by day and insomnia by night. Got misery and ecstasy. Dear Dr. Robbins what is my trouble? Only you can tell me. Please answer soon. I’m in bad shape.

Charlie

Charles Drew with his wife, Lenore, and their three daughters at the piano, 1947. National Library of Medicine, Profiles in Science Collection.

|

Like the Drews, famed historian Dr. John Hope Franklin and his wife, Aurelia Whittington Franklin, a librarian, also exchanged letters for years. The Franklins also took another step. They wrote a memoir together chronicling the history of their courtship and marriage.6 They begin with their first meeting at Fisk University in September 1931 and reflect on the ways their love for one another grew and evolved over the years. In this piece they write about cheering one another’s achievements, supporting one another in grief, and walking together as life unfolds. Perhaps their great insight on marriage is best displayed in the final words of the memoir where they candidly deny being role models and simply celebrate what they mean to each other:

As we look back on some forty-five years of married life, several cardinal factors—love, friendship, mutual respect, complete trust—stand out as major considerations. We do not mention these factors as keys to success, for we make no public qualitative judgment of our marriage. We know what we have meant to each other, and we do not designate the relationship as successful or unsuccessful. Indeed, were we to describe it in such terms, others might well have other opinions. The only thing that matters to us is that the relationship has been satisfactory and that is because we have worked hard to make it so. We never take anything for granted, nor do we assume that one’s actions should be acceptable to the other if the actions were taken unilaterally. The only unilateral action we feel free in taking is for one of us to do something in the hope that it will bring joy to the other. Full reward comes in the expression of gratitude on the part of the recipient. Our greatest joy has come in the sharing of experiences, whether a trip to Europe, Asia, or Africa or a tour of our flower garden at home. After all, it is the sharing that is the very essence of any close relationship.7

The Franklins celebrated 59 years of marriage together before Aurelia’s death in 1999.

Dr. John Hope Franklin and Mrs. Aurelia Franklin in their younger years

|

VI. Additional Resources

(a) Other couples may want to join the Franklins by writing a memoir of their marriage. A marriage enrichment ministry could guide couples in this endeavor by hosting a memoir workshop. Facilitators should provide helpful questions and invite couples to reflect on the joys and challenges of their journey together. If the writing process becomes too burdensome, a video memoir might serve as a suitable alternative. The video option will require providing comfortable seating, a relaxed setting, and good audiovisual equipment.

Here are a few starter questions:

1. How did you meet?

2. What were your first impressions of one another?

3. What did you do for fun together during your courtship?

4. What was the first major obstacle you faced as a couple?

5. What has your partner taught you about life? About yourself?

6. What are you most grateful for in your relationship?

7. Share a story about your partner.

8. When did the two of you share a big laugh together?

9. Reflect on a loss you mourned together.

10. What is your legacy as a couple?

These questions are by no means exhaustive, and they can serve as a helpful beginning for a couple’s memoir whether the chosen format is written or oral/video.

(b) Another resource for couples is the Presidential Anniversary Greeting. Couples celebrating a 50th wedding anniversary (or above) may receive a congratulatory letter from the President. While the request process takes at least six weeks’ advance notice, a letter from the White House can serve as a treasured memento for the couple and the family as a whole. Requests can be made through the White House.

(c) For further study on African American marriage consider:

|

Berlin, Ira and Leslie S. Rowland, eds. Families and Freedom: A Documentary History of African-American Kinship in The Civil War Era. New York: The New Press, 1997.

|

|

hooks, bell. All About Love: New Visions. New York: William Morrow & Co., 2000.

|

|

Segrave, Kerry. Lynchings of Women in the United States: The Recorded Cases, 1851–1946. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers, 2010.

|

|

Woods, Paula L. and Felix H. Liddell. I Hear A Symphony: African Americans Celebrate Love. New York: Doubleday, 1994.

|

Notes

1. Berlin, Ira, Marc Favreau, and Steven F. Miller, eds. Remembering Slavery: African Americans Talk About Their Personal Experiences of Slavery and Emancipation. New York: The New Press, 2007, p. 96.

2. Ibid., p. 124.

3. Berlin, Ira and Leslie S. Rowland, eds. Families and Freedom: A Documentary History of African-American Kinship in The Civil War Era. New York: The New Press, 1997. pp. 171–173.

4. Segrave, Kerry. Lynchings of Women in the United States: The Recorded Cases, 1851–1946. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers, 2010.

5. Families and Freedom. p. 23.

6. For a fuller collection of letters between Dr. Charles Drew and Lenore Robbins Drew, see Paula L. Woods and Felix H. Liddell. I Hear a Symphony: African Americans Celebrate Love. New York: Doubleday, 1994.

7. Woods, Paula L. and Felix H. Liddell. I Hear a Symphony: African Americans Celebrate Love. New York: Doubleday, 1994. pp. 181–182.

|