|

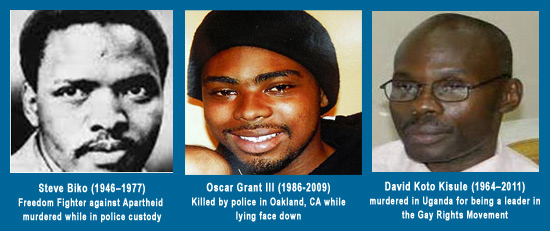

MARTYR'S SUNDAY/ALL SAINTS DAY

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Tuesday, November 1, 2011

Ernest A. Brooks III, Guest Cultural Resources Commentator

Associate Campus Minister, Martin Luther King Jr. International Chapel, Morehouse College, Atlanta, GA

I. Introduction

Martyrdom is the ultimate act of active nonviolent protest which has as its aim social transformation.

Committing oneself to death on the premise of principled conviction and uncompromising faith is the most

powerful response one can offer in the face of cowardice and hegemony that manifests itself as bigotry,

oppression, and other forms of systematic human degradation. While death is a fundamental component of

martyrdom, the essence of what it means to be a martyr extends beyond simply relinquishing one’s life in the face of danger or adversity.

In the Christian tradition, the label of martyr is a high honor ascribed to those individuals who gave

their lives in principled protest against the suppression of the Gospel of Christ, who committed themselves

to advancing the Gospel despite great personal costs, and those who dangerously served as advocates for human

freedom, justice, and equality as compelled by the ethical mandates of Jesus Christ.

The Anchor Bible Dictionary places the Christian notion of martyrdom in the context of the wider

Greco-Roman concept of the “Noble Death.”1 This concept of “Noble Death” is based on the premise

that it is most honorable to die in a sacrificial fashion on behalf and for the benefit of others. In this vein,

Jesus serves as the proto-typical martyr of the Christian tradition as he allowed himself to be subjected to physical

death on behalf and for the benefit of humanity. With this in mind, as we honor Christian martyrs who have “lived and

died for the faith,” it is imperative that the crucifixion of Christ and the worship of Jesus as the “sacrificial lamb of God” remain the focal point. While we celebrate men and women of profound faith and courage, including Stephen, we also must recognize that their acts of courage are but reflections of the paradigmatic sacrificial act of Jesus the Christ.

In the African American religious tradition, martyrdom is not only a matter of great spiritual import but also of great cultural and historic significance. We recognize as martyrs not only those who were killed as a result of overt battles of faith and evangelism in a classical sense, but also those who were evangelists of the social vision of Christ as recorded in Jesus’ inaugural sermon on Isaiah 58 and 61 where he declared, “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”

Books such as No Easy Victories: African Liberation and American Activists over a Half-century, 1950–2000 and Fools, Martyrs, Traitors: The Story of Martyrdom in the Western World chronicle historical and relatively contemporary instances of martyrdom in the quest for human equality and freedom and provide perspective on how the concept of martyrdom, the requirements for one to be considered a martyr, and the public perception of martyrdom had evolved over time.

II. Etymology

Martyr as employed in English and Latin is derived from the Greek Martus, which literally means witness. Common definitions of martyr reference such concepts as confession that provokes suffering and refusing to renounce conviction in the face of death. The contemporary understanding of a martyr as one who is killed because of their unwillingness to renounce a conviction of faith or as a result of action taken as a direct result of religious faith is rooted in the early Christian history of devotees of Christ, or witnesses, being subject to persecution and death for promoting and defending their religious beliefs. This notion of a Christian disciple serving as a witness emerged in the resurrected Christ’s final instructions to his disciples on the occasion of his ascension as recorded in Acts 1:8: “But you shall receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you shall be witnesses to Me in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the end of the earth.” In his bold refusal to back down from the charges of blasphemy leveled against him even in the face of death, Stephen is heralded as the paradigmatic witness or martyr.2

Stephen is a masculine name derived from the Greek Stephanos meaning literally “crown.”3 In some artistic renderings and iconography, Stephen is depicted with a crown above his head, hence the popular image of the “martyr’s crown.” The concept of the faithful being awarded a crown as a symbol of Christian achievement is not limited to martyrdom, as one could argue that all who are adopted as children of God in Christ are crowned to reflect their status in God’s eternal kingdom4; however, the stoning of Stephen, whose name means crown, connects the crowning of Christ as Lord with similar honor reserved for those who commit their lives to being witness for the gospel of Christ in a broader sense.5 Just as Jesus was crowned with thorns and crucified prior to being crowned with glory and honor on his ascension, so too are those celebrated as martyrs subject to ridicule, scorn, and violence prior to being feted with high honor.

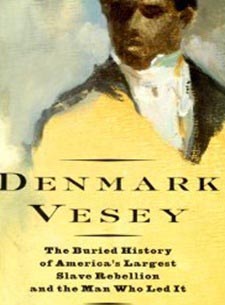

III. Biographical Reflection—Denmark Vesey

|

Denmark Vesey (1767–1822) was a South Carolina slave of Caribbean background who planned what would have been, if successful, one of the largest American slave revolts. Vesey purchased his own freedom from slavery in November 1799 for $600 after winning $1500 in the Charleston, SC lottery. The remaining $900 was not sufficient to purchase the freedom of his family, which inflamed Vesey’s determination to end slavery. Vesey, a member of the segregated Second Presbyterian Church in Charleston, joined approximately 4,000 other black members of Charleston churches with segregated membership policies in an assertion of spiritual agency by leaving these churches to found their own religious institutions. Commencing around 1815, according to various sources,6 this exodus from segregated religious institutions led to the founding of several African American-led congregations in Charleston—including the African Methodist Episcopal Church of Charleston (organized in 1815, incorporated in 1818) under the leadership of the Rev. Morris Brown, a devotee of Rev. Richard Allen of Philadelphia, founder of the AME Church. As a founding member of the AME Church of Charleston, Vesey served as a lay preacher and class leader, hosting small groups in his home for study and exhortation.

It is in this context that the connection between Vesey’s faith and his call to armed revolution is made explicit, providing the foundation of the case for his recognition as a Christian martyr. In the book Slave Culture, P. Sterling Stuckey, noted professor of American history and expert in the history of American slavery, grounds Vesey’s radical vision of liberation through revolt in the nascent Black liberation theology and African nationalism that featured prominently in the religious life of those who left white religious institutions with the intent of carving out formative space for their unique blend of African social consciousness, hope for physical liberation, and biblical imagery of God as deliverer and protector known as ‘Black Religion.’ Stuckey notes, “At the church and in his home, Vesey preached on the Bible, likening the Negroes to the children of Israel, and quoting passages which authorized slaves to massacre their masters. Joshua, chapter 4, verse 21, was a favorite citation: ‘And they utterly destroyed all that was in the city, both man and woman, young and old, and ox, and sheep, and ass, with the edge of the sword.”7

Vesey coupled his theology of revolutionary liberation rooted in the Old Testament Exodus narrative and prophetic tradition with the African tribal theology of an Angolan priest named Gullah Jack, who was also a member of the AME Church of Charleston. Although a member of the church, Gullah Jack continued to serve as a communal healer and spirit conjurer, blending the Afro-Christianity of the church with the traditional African practices of which many in the Charleston slave and free black community were still devoted.8 Vesey and Jack spent the early months of 1822 crafting a strategy to commandeer the arsenals and vessels of the Port of Charleston and enlisting as many slaves as they could in their militia to accomplish their revolutionary coup.

While Vesey was able to use the combination of his Christian preaching with strong liberative overtones and the traditional African ritual of Gullah Jack to build a proverbial army of thousands ready to destroy any vestige of slavery and white authority in Charleston and the surrounding territory, not all black Charlestonians were supportive of Vesey and his revolutionary plans. Douglas Egerton notes in He Shall Go Out Free: The Lives of Denmark Vesey that Vesey was “convinced . . . that the same God who spoke to him did not speak to the accomodationist AME leadership” and took great pains to keep his plans from Rev. Morris Brown, pastor of the AME Church of Charleston in fear of reprisal and condemnation.9 While Vesey was successful in avoiding Rev. Brown, he was unable to completely assuage the concerns of some in his own ranks who wrestled with the question of whether bloodshed and mass murder was the most appropriate manner to achieve liberation. While Vesey made the case through his preaching that the Old Testament was rife with examples of God commissioning oppressed people to fight for their liberation, even through military battle and bloodshed, others in the church grounded their faith in the Christian ethic of love for one’s neighbor and refused to believe that God would ordain liberation through such violent means. One such individual in the latter camp was George Wilson, a slave and fellow session leader in the AME Church of Charleston. When one of the members of Wilson’s class revealed their uneasiness with Vesey’s plans, Wilson revealed the plot to his slave-master, effectively thwarting the rebellion and sealing Vesey’s fate. Vesey was executed by hanging on July 2, 1822, 12 days before the scheduled date of his rebellion. In total, 32 others identified as leaders or organizers of the rebellion were also killed.10

The story of Denmark Vesey highlights the subjective nature of identifying someone as a Christian martyr. Even in his church, the African Methodist Episcopal Church of Charleston, and among his contemporaries, there was debate about whether Vesey should be heralded as a Christian martyr who was killed for seeking to live out the demand of his faith to liberate his fellow men and women from slavery or mourned as a wayward ideologue who committed himself to a bloody revolutionary plot with no spiritual justification or expectation of success. Throughout Christian history the application of the title “martyr” has been a source of much debate and disagreement.11 While the authority to canonize or beatify individuals has been long vested in the apostolic leadership of institutions with episcopal polity, perspectives on martyrdom differ widely in any given denominational, cultural, ideological, or generational context.

One of the most salient examples of this phenomenon in recent history has been the continuing conversation concerning the best way to honor the life and legacy of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. One would be hard pressed to find individuals in the African American Christian religious tradition who would not herald Dr. King as a martyr in the best of the Christian tradition; however, this has not always been the case in the wider Christian community, with reticence and discomfort with those who claim a mandate of Christian faith for social transformation. With this being the case, we in the African American religious tradition cannot afford to wait for official church councils and resolutions to determine who our martyrs are and what in our unique social and religious history compels one to “live and die for the faith.”

Questions for Discussion

1. Would you consider Denmark Vesey a martyr? Why or why not?

2. Is there anything that distinguishes the action of Vesey from others identified as Christian martyrs such as Stephen or even Jesus himself?

3. It was noted that Vesey preached almost exclusively from the Old Testament, citing the story of the Exodus and the prophetic calls for justice through the taking up of arms as justification for his revolutionary plot. What is our responsibility as Christians (and Christian preachers) concerning our use of biblical texts? How do we balance calls for justice through force with commands to “love those who persecute you” and “turn the other cheek”?

4. Are there others in African American history whom you would identify as martyrs? What similarities or differences do they have with Denmark Vesey?

III. Art and Poetry

Artistic Interpretation

“The Stoning of St. Stephen” by Rembrandt

There is a plethora of artistic renderings of Stephen and the occasion of his martyrdom as described in Acts 7. One of the more intricate of these artistic works is “The Stoning of St. Stephen” by noted 17th century Dutch painter Rembrandt van Rijn. Rembrandt, known for his ability to capture both the spirit of and details of historical moments in paint, is responsible for in excess of 300 artistic works depicting biblical subjects and scenes. “The Stoning of St. Stephen,” completed in 1625, with its depth and attention to narrative detail is exemplary of the Rembrandt style.12

“The Stoning of St. Stephen” serves as an artistic commentary on Acts 7:52-60 in a manner similar to the allegorical tradition of the Early Church Fathers.13 Not only does Rembrandt artistically depict the scene as recorded narratively in the biblical text, he also adds his own subjective interpretive elements while leaving space to accommodate the imagination and perspective of others. One of the most apparent features of the painting is the use of lighting to draw attention to Stephen, who is depicted adorned in traditional 17th century deacon’s attire, on his knees looking upward to heaven as the mob of accusers surround him with stones in hand. This aspect of the artistic scene corresponds to Acts 7:55a: “But he, being full of the Holy Spirit, gazed into heaven and saw the glory of God.” In the distance (upper right quadrant of the painting), Jerusalem is depicted as a city with great architecture, however overgrown, dark, and antiquated. There are several groups of people depicted in the painting including the mob actively engaged in the stoning of Stephen in the foreground; a group commonly identified as priests in the right background (possibly the council of the high priest as referenced in Acts 6:12-7:1); individuals with expressions of shock and concern, possibly fellow Christians, in the center background; and a man on a horse seemingly acting as overseer of the actions of the mob in the left foreground. The shadowy figure on horseback overseeing the stoning of Stephen is presumably Saul, who is referenced in verse 58, “and they cast him out of the city and stoned him. And the witnesses laid down their clothes at the feet of a young man named Saul.” While there is no reference in this passage to Saul being on horseback, this artistic feature could be an allusion to the dramatic conversion of Saul from the preeminent persecutor of Christians to Paul an apostle of Christ, prolific pastoral writer, and missionary leader (Acts 9).

Poetry

a. The Martyr by Herman Melville

Good Friday was the day

Of the prodigy and crime,

When they killed him in his pity,

When they killed him in his prime

Of clemency and calm—

When with yearning he was filled

To redeem the evil-willed,

And, though conqueror, be kind;

But they killed him in his kindness,

In their madness and their blindness,

And they killed him from behind.

There is sobbing of the strong,

And a pall upon the land;

But the People in their weeping

Bare the iron hand:

Beware the People weeping

When they bare the iron hand.

He lieth in his blood—

The father in his face;

They have killed him, the Forgiver—

The Avenger takes his place,

The Avenger wisely stern,

Who in righteousness shall do

What the heavens call him to,

And the parricides remand;

For they killed him in his kindness,

In their madness and their blindness,

And his blood is on their hand.

There is sobbing of the strong,

And a pall upon the land;

But the People in their weeping

Bare the iron hand:

Beware the People weeping

When they bare the iron hand.14

In The Martyr, famed American novelist, essayist, and poet Herman Melville draws our attention to the crucifixion of Christ as the ultimate example of martyrdom. Through rich poetic imagery and descriptive language, Melville makes the point that it was not the event of Jesus’ crucifixion alone that makes him the ultimate martyr, but also the blameless life that he lived and the divine calling that he fulfilled. Furthermore, Melville contrasts the kindness and righteousness of Jesus with the blindness and madness of his persecutors. Finally, Melville connects the very personal act of the murder of Jesus’ person with the resulting lament of the community (“And a pall upon the land”) and a warning to beware of the fact that all who seem to mourn are not themselves without complicity.

This poem, or parts of it, can be employed in the preaching moment or in a teaching moment to achieve several ends:

- To express the centrality of Jesus’ crucifixion in the Christian understanding of martyrdom.

- To remind the worshipping community, with vivid imagery, that martyrdom, while it is to be celebrated, comes as a result of the ultimate human sacrifice—that of life itself.

- To contextualize the particular act of a martyr with the wider Christian mission of individual redemption and communal transformation.

IV. Songs That Speak to the Moment

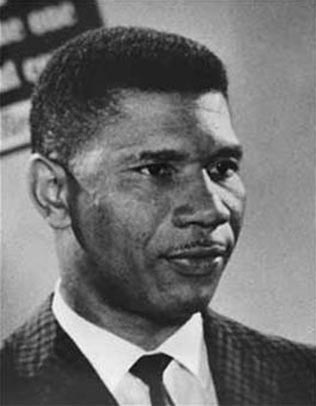

To reflect the rich diversity of musical styles and genres available to us and to promote the practice of exposing our congregations to that rich diversity in our sacred and popular musical traditions, I have identified four songs that directly or indirectly consider themes related to martyrdom: “Oh Freedom,” a traditional Negro spiritual; “Father I Stretch My Hands to Thee,” a widely published hymn with an arrangement unique to the African American worship experience; “Battlefield,” a modern gospel song in the choral tradition; and “Ballad of Medgar Evers,” an American folk song written in memory of slain Mississippi civil rights leader Medgar Evers.

(a) Spiritual

Hear the song “Oh, Freedom” performed by The Princely Players (with pictures from the Library of Congress National Archives Slavery Collection).

Oh Freedom

Oh freedom,

Oh freedom,

Oh freedom over me, over me.

And before I’d be a slave,

I’d be buried in my grave,

And go home to my Lord and be free.

No more mo’nin,

No more mo’nin,

No more mo’nin over me.

And before I’d be a slave,

I’d be buried in my grave,

And go home to my Lord and be free.

No more slavery,

No more slavery,

No more slavery over me.

And before I’d be a slave,

I’d be buried in my grave,

And go home to my Lord and be free.

No more weeping,

No more weeping,

No more weeping over me.

And before I’d be a slave,

I’d be buried in my grave,

And go home to my Lord and be free.

There’ll be singing,

There’ll be singing,

There’ll be singing over me.

And before I’d be a slave,

I’d be buried in my grave,

And go home to my Lord and be free.15

(b) Hymn

Father I Stretch My Hands to Thee

Father, I stretch my hands to Thee;

No other help I know.

If Thou withdraw Thyself from me,

O! whither shall I go?

What did Thine only Son endure,

Before I drew my breath!

What pain, what labor, to secure

My soul from endless death!

Surely Thou canst not let me die;

O speak and I shall live;

And here I will unwearied lie,

Till Thou Thy Spirit give.

Author of faith! to Thee I lift

My weary, longing eyes:

O let me now receive that gift!

My soul without it dies.16

(c) Gospel

Battlefield

I’m a soldier on the battlefield and I’m fighting,

(fighting for the Lord).

I promised Him I would serve Him until I die, and I’m fighting,

(fighting for the Lord).

On this Christian journey, I’ve had heartaches and pain,

sunshine and rain, but I’m fighting,

(fighting for the Lord).

I’ve been up and I’ve been down but I’ll never turn around, cause I’m fighting

(fighting for the Lord)

Bridge:

If I hold out (4x),

then I know (I’ll get my crown).

Vamp:

I’m on the battlefield fighting for the Lord.

Ending:

(I promised Him that I,

would serve Him til I die and I’m fighting),

fighting for the Lord.17

(d) See the video of Phil Ochs singing the song “Ballad of Medgar Evers.” The words for the song are below.

Ballad of Medgar Evers (Too Many Martyrs)

|

Medgar Evers

|

In the state of Mississippi many years ago

A boy of 14 years got a taste of southern law

He saw his friend a hanging and his color was his crime

And the blood upon his jacket left a brand upon his mind

CHORUS:

Too many martyrs and too many dead

Too many lies too many empty words were said

Too many times for too many angry men

Oh let it never be again

His name was Medgar Evers and he walked his road alone

Like Emmett Till and thousands more whose names we’ll never know

They tried to burn his home and they beat him to the ground

But deep inside they both knew what it took to bring him down

Chorus

The killer waited by his home hidden by the night

As Evers stepped out from his car into the rifle sight

he slowly squeezed the trigger, the bullet left his side

It struck the heart of every man when Evers fell and died.

Chorus

And they laid him in his grave while the bugle sounded clear

laid him in his grave when the victory was near

While we waited for the future for freedom through the land

The country gained a killer and the country lost a man

Chorus18

V. Resources on Christian Martyrdom & Martyrdom in the African American Experience

Magazine Articles

- Ebony Magazine, August 1975 Special Issue: The Bicentennial: 200 Years of Black Trials and Triumph, “Martyrs for Black Freedom,” pp. 138–141. Available online from Google Books: http://books.google.com/books?id=znUlZTIWfrEC&lpg=PA138&dq=black%20martyr s%20book&pg=PA1#v=onepage&q=black%20martyrs%20book&f=false

- Ebony Magazine, February 1990, “Remembering the Martyrs of the Movement: The Civil Rights Memorial honors 40 who died in America for basic freedoms,” pp. 58–62. Available online from Google Books: http://books.google.com/books?id=p8wDAAAAMBAJ&lpg=PA58& ;ots=O7qeh2CHrM&dq= ebony%20Remembering%20the%20martyrs%20of %20the %20movement%3A&pg=PA62#v=onepage&q=ebony%20Remembering %20the%20martyrs%20of%20the%20movement:&f=false

- Time Magazine, March 7, 2007, “Early Christianity’s Martyrdom Debate” by David Van Biema. Available at http://www.time.com/time/arts/article/0,8599,1596991,00.html

Web Resources

Books

- Egerton, Douglas R. He Shall Go Free: The Lives of Denmark Vesey. Madison, Wisconsin: Madison House, 1999.

- Foxe, John. Foxe’s Christian Martyrs. Gainesville: Bridge-Logos, 2001.

- Minter, William, Gail Hovey, and Charles Cobb Jr. No Easy Victories: African liberation and American activists over a half-century, 1950–2000. Trenton: Africa World Press, 2007.

- Smith, Lacey Baldwin. Fools, Martyrs, Traitors: The Story of Martyrdom in the Western World. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1999.

- Stuckey, P. Sterling. Slave Culture. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Terrell, JoAnne Marie. Power in the Blood? The Cross in the African American Experience. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1998.

- Water, Mark. The New Encyclopedia of Christian Martyrs. Ada: Baker Books, 2001.

- Wood, Amy Louise. Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America (1890–1940). Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Notes

1. Anchor Bible Dictionary, Vol. IV, “Martyr, Martyrdom” New York: Doubleday, 1992, 574–578.

2. Bowker, John. “Martyr.” The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions, 1997. Online location: http://www.encyclopedia.com. Also, “Martyr.” Wikitionary. Online location: http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/martyr

3. Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible. “Stephanos,” #4736. Online location: http://strongsnumbers.com/greek/4736.htm

4. Galatians 4:1-7; Hebrews 2:1-18; 1 Peter 2:9; Revelation 2:10.

5. “Martyrdom of St. Stephen.” Online location: http://www.ststephen.webhero.com/martyrdom_of_st_stephen.htm

6. Public Broadcasting Systems, “This Far by Faith.” “Denmark Vesey.” Online location: http://www.pbs.org/thisfarbyfaith/people/denmark_vesey.html. Also, Egerton, Douglas R., He Shall Go Free: The Lives of Denmark Vesey. Madison: Madison House, 1999, 108–111.

7. Stuckey, P. Sterling. Slave Culture. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987, 48–49.

8. “This Far by Faith.” Ibid.

9. He Shall Go Free. Ibid., 145.

10. “This Far by Faith.” Ibid.

11. Van Biema, David. “Early Christianity’s Martyrdom Debate.” Time Magazine. March 7, 2007. Online location: http://www.time.com/time/arts/article/0,8599,1596991,00.html

12. The Stoning of St. Stephen. Online location: http://www.artbible.info/art/large/682.html

13. For primary source material on the allegorical commentary tradition of the Patristic period, see the 27-volume Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture. Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 1998–2008.

14. Melville, Herman. The Martyr. Online location: http://www.poetry-archive.com/m/the_martyr.html

15. “Oh Freedom.” Online location: http://www.ed.uiuc.edu/courses/ci407ss/ohfreedom.html

16. Wesley, Charles. “Father I Stretch My Hands to Thee.” Arr. by Nolan Williams, Jr. Location: African American Heritage Hymnal. Chicago, IL: GIA Publications, 2001. #127

17. Hutchins, Norman. “Battlefield.” Online location: http://www.lyricsmania.com/battlefield_lyrics_norman_hutchins.html

18. Ochs, Phil. “Ballad of Medgar Evers” (Too Many Martyrs). Online location: http://www.cowboylyrics.com/lyrics/ochs-phil/too-many-martyrs-11440.html

|