|

Guest Writer for This Unit: Ethel Walker, elementary school teacher for nineteen years and ordained clergy, Oakland, CA

The unit you are viewing, Children’s Day (Birth—Age 12) Rites of Passage, is a compact unit. This means that it is not a complete commentary of the Scripture(s) selected for this day on the calendar, nor does it have a full, supporting cultural resource unit and worship unit. Instead, to enliven the imagination of preachers and teachers, we have provided a sermonic outline, songs, suggested books, and suggested articles, links, and videos. For additional information see Children’s Day in the archives of the Lectionary for 2008–2010. In 2011 the African American Lectionary began posting compact units for moments on its liturgical calendar.

I. Description of the Liturgical Moment

A child not reared by the Church will be reared by the world.

“Find sustenance in your origins . . . . You hearers, seers, imaginers, thinkers, rememberers, you prophets called to communicate truths of the living way to a people fascinated unto death . . . . The eyes of the seers should range far into purposes. The ears of the hearers should listen far toward origins. The utterers’ voice should make knowledge of the way, of heard sounds and visions seen, the voice of utterers should make this knowledge inevitable, impossible to lose.”1

This Sunday, Children’s Day (birth–age 12) is the liturgical moment of focus. On this Sunday, the emphasis is on training children the right way and doing training sufficient so that they will not depart from it when they are old. In addition to the theological information that grows out of Proverbs 22:6, on this Children’s Sunday the Lectionary is advocating for rites of passage programs (ROPP) as an effective way for the Black Church to train black children to love God; uplift their families; find, embrace, and live out their purpose; and become exemplary models for others to do all of the same.

Although Rites of Passage programs are not new and have been used for children, teens, and adults, our focus is on young children (birth–age 12). My experience with ROPP and the literature has convinced me that the components of a typical, strong rites of passage program for children will likely be most useful for ages 5–12. However, this does not prevent churches from beginning to use ROPP principles as soon as a child can speak. Then, once a child comes of age, they will move naturally into a ROPP.

What is a rites of passage program? Rites of passage programs designed for and operated by African Americans have been around in the United States since the 1960s and most give credit for their existence in the United States to the cultural nationalist or Pan-African movement of the 1960s–1970s.2 The African concept of rites of passage or initiation, which has its roots in ancient Kemet (Egypt), undergirds (in some way) all African American rites of passage programs. According to Nsenga Warfield-Coppock, a Washington, D.C.-based psychologist who has studied ROPP,

A rite is a ceremony or celebration. Passage refers to the movement from one state to another. Thus, the adolescent rite of passage is a supervised developmental and educational process whose goal is to assist young people in attaining the knowledge and accepting the responsibilities, privileges, and duties of an adult member of a society. . . .3 The rites of passage can thus be considered a social and cultural “inoculation” process that facilitates healthy, African-centered development among African American youth and protects them against the ravages of a racist, sexist, capitalist, and oppressive society. Most importantly, it prepares them physically, mentally, and spiritually for active resistance and struggle against the seductive lure of the American Way.4

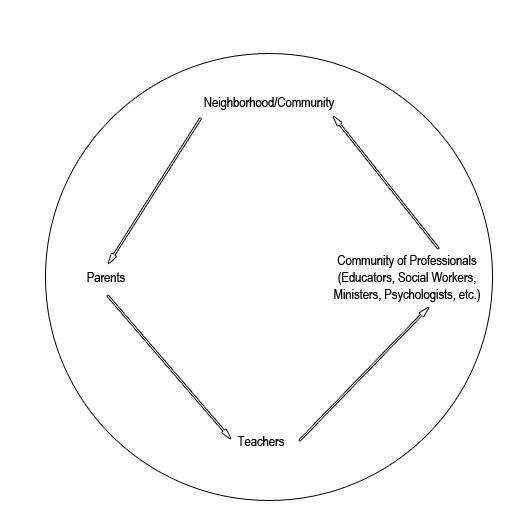

In wholehearted agreement with Warfield-Coppock, when I speak of training African American children in the right way, so that they will not depart from this training when they are old, I am speaking of African American churches and parents first, and other interested parties of good-will second, providing the training needed. Churches that operate ROPP must ensure that they have an African American pedagogical approach that is holistic and best suited to the learning styles of those served. Churches need to ensure that students can see themselves in the curriculum, and African American administrators are needed.

Churches are needed to stand in the gap. Those in power have already killed public housing, public health, public aid for the poor, and public education. In order to have a nation of children rise who will stand up for those who are powerless and who continue to lose, the black Church must begin to help youth mediate their experiences and learn how to control the world around them.

II. Children’s Day Rites of Passage: Sermonic Outline

A. Sermonic Focus Text(s): Proverbs 22:6a (New Revised Standard Version)

Train children in the right way, and when old, they will not stray.

B. Possible Titles

i. Training Children Is Our Responsibility

ii. Train Them Black or They Will Fall Back

iii. To Train or Not to Train Black Children

C. Point of Exegetical Inquiry

| In any text there can be several words or phrases that require significant exegetical inquiry. One exegetical inquiry raised by this text is how shall children be trained? I attempted to address this in the introduction and will discuss it further below. Second, what of the exceptions to Proverbs 22:6? What are Christian parents to do who believe that they have done all that they can do to rear their children well yet their children turn out to be dysfunctional and always in trouble? |

|

A proverb is not a precept. A precept is a truth stated in absolute terms. Proverbs are true but the same outcome is not always gained when a proverb is enacted. Precepts are absolutes; you always get the same outcome. If one comes across a proverb that he or she believes is always true, it will not always be true as a proverb. If it is a proverb backed up by other Scriptures, likely the additional Scriptures are where one should look for what makes it always true. Proverbs 22:6 does not have other Scriptures that will make it true in every case. However, although I cannot guarantee that each parent who trains a child in the ways of God will produce a child who will not stray from that training, I guarantee that those parents who provide no training ought never expect children who are God-fearing and obedient to God and God’s word.

A second point of exegetical focus should be the fact that careful consideration suggests, as I was taught in seminary, that the verb “to train” if speaking of people (not inanimate objects) refers to a bestowal of status and responsibility. The noun translated “child” denotes the status of a later adolescent rather than a child. “In the way that he should go” is best understood as “according to what is expected. The original intent of this verse addresses a later adolescent’s entrance into his [or her] place into society.”5 Also, status, not age, is more often the focus when the word “child” (rfana) is used throughout Scripture.6

III. Introduction

Have you heard people say, “It’s harder to raise children now; things are so different.” Well, yes and no. Yes, it’s harder to rear godly children in family systems that are led by poor, only functionally literate, single women who are without familial and community support (literally and figuratively). Yes, it’s harder to rear black children when they have fewer institutions and businesses that they can look to for example and uplift. Yes, it’s harder to rear black children in environments that are filled with failing public schools, crime, and drugs. So, why is there a no? The no is because 1. Things were different during slavery and Reconstruction, yet one does not typically read of the difficulties in rearing God-fearing children that are so prevalent now. 2. For hundreds of years poor, only functionally literate, black mothers (after husbands and even children were sold or killed at the whim of slave masters) had to rear God-fearing children alone and did. 3. I say no because for much of our early history in America, it was illegal for black children to learn to read. When it was legal, blacks learned (when not laboring in fields and elsewhere) in sub-standard schools, but at least had black teachers, and during this period we still started churches, built businesses, and commanded unified communities.

So, I believe that although parents, especially single parents as I was, are faced with ridiculously difficult obstacles to rearing God-fearing children, now having a child is a choice, more than it has ever been. Accordingly, those who choose to have children have the responsibility to rear them in the fear and admonition of God, no excuses, no exceptions. So, what shall preachers urge as training components?

Dr. Asa Hillard III said in his book The Maroon within Us: Selected Essays on African American Community Socialization, “Education is concerned with the construction/reconstruction of identity both group and individual.” He said further, “We must end corrosive views,”7 by which he explained:

We . . . equate sophisticated technology with culture, believing that such technology is exclusively European and that to affirm African culture is to reject technology. 2. We . . . equate European culture with wealth and African/African American culture with poverty. 3. We . . . equate self-affirmation with hatred of others. 4. We . . . equate religion with particular forms of European interpretations of Christianity and have not seen our own people as religious.8

With these thoughts in mind, I would suggest that in a rites of passage program for children, the Black Church must be the one to teach with unconditional love, total conviction, and high intellectual acumen:

1. The ancient period of our ancestors. This was the period of Thutmoses III, the greatest conqueror; Akhenaton, the world’s first apostle of nonviolence; Hatsheput, the most famous woman to rule Kemet or any nation as a queen; and the popular but inconsequential young pharaoh, King Tutankhamen.”9

2. They must teach that this period was interrupted by the maafa or disaster. Ani (1994) introduced this Swahili term in the book Yurugu: An African-Centered Critique of European Cultural Thought and Behavior, which describes the forcible interruption of African civilization as the maafa. Exceeding previous Greek and Roman incursions, European conquest and hegemony was totalizing. By the time of the Berlin Conference (1885), indigenous African institutions were being obliterated. The maafa continues, as does the destruction of African people’s culture.10

3. Since the maafa continues, we must also teach our children the following information and then train them so that they become change agents. It has already been summed up so well by the late historian, educator, and psychologist Dr. Asa Hillard III. He said that black folks have:

No unified spiritual base that respects and compliments our different religion;

No global view of ourselves as one people;

No geopolitical view of our condition a people;

No global strategy (or even local strategy) for our uplift as a people;

No collective aim;

No structures for socializing the masses of our children; and

No structure for communicating these things to our masses.”11

I would add that we need a way of communicating in a totalizing fashion the effects of the maafa and Euro-western culture on our views of human sexuality, thus explaining the high level of homophobia in our community.

Dr. Carol Lee, who served as director for a successful African-centered school for more than a decade and is a professor at Northwestern University in Chicago, in section VII below provides more curriculum approaches and substance that would benefit any rites of passage curriculum and program. Your church can decide if it needs a ROPP for girls only and one for boys only or whether the two groups should be taught together throughout a ROPP or brought together for select components of a ROPP. Your church may not have enough people who can competently operate a ROPP. In this case, you may want to offer volunteers to assist other successful rites of passage program and send your kids there and then conclude the program with a community-wide celebration by two or more churches. Remember, collaboration is in keeping with the Afri-centric notion of the village rearing all children. Also, see sections X and XII for examples of rites of passage programs and section XI for books that your church can use to establish its own rites of passage program or to strengthen another program with which you can work collaboratively.

IV. Moves/Points

Move/Point One – Ancient Israelites Made Training of Children Important

a. Offer brief exegesis of the words “train” and “child” in Proverbs 26a;

b. Israelite children were trained in customs and the Torah; and

c. The Black Church must train children in black culture and the Bible.

Move/Point Two – A Rite of Passage Program Will Help Train Children

a. The training must be comprehensive and thorough;

b. Without an understanding of their culture our children are doomed; and

c. A public education will not get the job done.

Move/Point Three – They Will Not Depart When They Are Old If:

a. They are trained in the right way;

b. The Church and parents cooperate in the training; and

c. The training is spiritually focused and Afro-centric.

V. Celebration

When Black children are trained to know their identity (that they are descendants of African children of God such as Thutmoses III, the greatest conqueror; Akhenaton, the world’s first apostle of nonviolence; Hatsheput, the most famous woman to rule Kemet or any nation), trained to know their God-given purpose, and given direction on how to share their identity and the gifts through which they will release their purpose and genius on the world, we will see something amazing happen. We will see the next and greater Thutmoses and the next and greater Barack, the next Akhenaton and the next and greater Martin Luther King Jr., the next Hatsheput and the next and greater Barbara Jordan. This is the genius that lies within our children. So we shall saturate their lives with so much God, so much love, so much knowledge, and so many holy and righteous examples, until their genius, against all odds, is fully released.

We shout right now for the geniuses who are in our midst and those who will be revealed. Thank you, God; we need them, God. Praise you, God; so much depends on them. We love you, God; because from generation to generation, we are not deceived, you are faithful to us. Ashay. Ashay. Ashay.

VI. Sounds, Sights, and Colors in This Passage

| Sounds: |

The voices of children at play; children tapping technological tablets; children turning the books of pages; children reciting the Bible and the words of their ancestors; children speaking their dream for a better world;

|

| Sights: |

Children standing tall with self-confidence; well-groomed, well-fed, and bright-eyed children learning of their culture and that they are global citizens; children praying; children embracing their parents; children respecting their teachers; and

|

| Colors: |

Pink, blue, red, black, and green. |

VII. Training Children Using Principles from Successful Rites of Passage Programs

Carol Lee recommends the following value system for Rites of Passage training.12

Lee asserts that to teach using an Afri-centric pedagogy requires:

- The social ethics of African culture as exemplified in Kemetic society and education. Kemetic (Egyptian) education is the parent of western education.13

- The history of the African continent and Diaspora;

- The need for political and community organizing within the African American community;

- Child development principles that are relevant to the positive and productive growth of African American children;

- African contributions in science, mathematics, literature, the arts, and the societal organizations;

- Teaching techniques that are socially interactive, holistic, and positively affective;

- The need for continuous personal study and critical thinking;

- More than knowledge of Black history and culture;

- Acceptance of the African principle that “children are the reward of life”;

- A teacher sees his or her future symbolically linked to the development of students;

- A teacher is well-read in a Black Classic Education;

- A teacher is well-read in contemporary child development theories and can review the theories critically; and

- Teachers must learn more than they believe possible and teach children and parents that they are to do the same.14

I believe that to design a curriculum undergirded by many of the former principles would go a long way in revitalizing Christian education in the black church for children, teens, and young adults.

VIII. Illustrations and Parenting Wit and Wisdom

If We Will Get It Right, They Will Get It Right

After a boy turned in his homework, the teacher said, “This is terrible! How can one person make so many mistakes?” “One didn’t,” the boy answered. “My dad helped me.” Our children will do as we teach them. If we get it wrong, they’ll get it wrong. But if we’ll train them according to God’s Word, we’ll get it right—and eventually they’ll get it right too. “Train up a child in the way he should go, even when he is old he will not depart from it” (Proverbs 22:6).

Parenting Wit & Wisdom

- If it was going to be easy, it never would have started with something called labor.

- Shouting to make your children obey is like using the horn to steer your car, and you get about the same results.

- Grandparents are similar to a piece of string—handy to have around and easily wrapped around the fingers of grandchildren.

- An alarm clock is a device for awakening people who don’t have small children.

—Andy Chaps, “The Funnies”

Mom Was Right After All

“The more I go through parenting, the more I say I owe my mother an apology.”

Eyes & Ears

“Don’t worry that children never listen to you. Worry that they’re always watching you.”

IX. Songs to Accompany This Sermon

A. Well-known Song(s)

- God Made Me. By Dorcus Thigpen

- Anybody Here. By Deitrick Haddon

- Deep Love. By Charles Jenkins

B. Modern Song(s) (Written between 2000–2011)

- I Am a Promise. By William Gaither and Gloria Gaither

- God’s by Design. By Robert Barone and Jeff Hardy

C. Spiritual(s)

- A Child of the King. By Harriet E. Buell. Arr. by Valeria A. Foster

- Learning to Lean. By John Stallings. Arr. by Evelyn Simpson-Curenton

- We’re Growing. By Evelyn Reynolds. Arr. by Nolan Williams, Jr.

- Greater (I Can Do All Things). By Twila LaBar and Jeff Ferguson

D. Liturgical Dance Music

- Bow Down My Child. By Robin Dalton, Lauren Denise Carpenter, Bryan Scott, and Sidney Scott

- Higher. By James White

X. Videos, Audio, and/or Interactive Media

XI. Books to Assist in Preparing Sermons, Bible Studies, and/or Worship Services Related to Children’s Day with a focus on Rites of Passage efforts

|

Hill Jr., Paul. Coming of Age: African American Male Rites-of-Passage. Sauk Village, IL: African American Images, 1997.

|

|

Lewis, Mary C. Herstory: Black Female Rites of Passage. Sauk Village, IL: African American Images, 1998.

|

|

McNair, Chris. Young Lions: Christian Rites of Passage for African American Young Men. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 2001.

|

|

White, Richelle B. Daughters of Imani—Planning Guide: Christian Rites of Passage for African American Girls. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 2005.

|

|

Maye, Marilyn. Orita: Rites of Passage for Youth of African Descent in America. Houston, TX: Faith Works, 2000.

|

|

Winans, CeCe. Always Sisters: Becoming the Princess You Were Created to Be. Brentwood, TN: Howard Books, 2007.

|

XII. Links to Helpful Websites for Children’s Day (Rites of Passage)

XIII. Notes for Select Songs

A. Well-known Song(s)

- God Made Me. By Dorcus Thigpen

Location:

Mississippi Children’s Choir. Children of the King. Jackson, MS: Malaco Records, 1992.

- Anybody Here. By Deitrick Haddon

Location:

Haddon, Deitrick & Voices of Unity. Chain Breaker. Indianapolis, IN: Tyscot Records, 1999.

- Deep Love. By Charles Jenkins

Location:

Joshua’s Troop. Joshua’s Troop. Indianapolis, IN: Tyscot Records, 2000.

B. Modern Song(s) (Written between 2005–2011)

- I Am a Promise. By William Gaither and Gloria Gaither

Location:

Veggie Tales. Veggie Tales Worship Songs. Franklin, TN: Big Idea, Inc., 2006.

- God’s by Design. By Robert Barone and Jeff Hardy

Location:

Boys & Girls Choir of Harlem. God’s by Design. New York, NY: Comin’ Atcha Distribution Group, 2005.

C. Spiritual(s)

- A Child of the King. By Harriet E. Buell. Arr. by Valeria A. Foster

Location:

African American Heritage Hymnal. Chicago, IL: GIA Publications, 2001. #125

- Learning to Lean. By John Stallings. Arr. by Evelyn Simpson-Curenton

Location:

Zion Still Sings for Every Generation. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 2007. #167

- We’re Growing. By Evelyn Reynolds. Arr. by Nolan Williams, Jr.

Location:

African American Heritage Hymnal. #618

- Greater (I Can Do All Things). By Twila LaBar and Jeff Ferguson

Location:

Zion Still Sings. #44

D. Liturgical Dance Music

- Bow Down My Child. By Robin Dalton, Lauren Denise Carpenter, Bryan Scott, and Sidney Scott

Location:

Jesus Gang. Live My Life for You. Indianapolis, IN: Tyscot Records, 2000.

- Higher. By James White

Location:

Georgia Mass Choir. Higher. Jackson, MS: Savoy Records, 1999.

Notes

1. Armah, A.K. Two Thousand Seasons. Chicago: Third World Press, 1979. p. xiii.

2. Warfield-Coppock, Nsenga. “The Rites of Passage Movement: A Resurgence of African-Centered Practices for Socializing African American Youth.” The Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 61, No. 4 (Autumn 1992), p. 474. Online location: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2295365 accessed 18 October 2011

3. Ibid., p. 472.

4. Ibid., p. 474.

5. Hildebrandt, Ted. “Proverbs 22:6a: Train Up a Child?” Grace Theological Journal 9.1 (1988). pp. 3–19.

6. Ibid.

7. Hillard, Asa, III. The Maroon within Us: Selected Essays on African American Community Socialization. Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 1995. pp. 57–58.

8. Watkins, William H. “Asa Grant Hilliard: Scholar Supreme.” American Educational Research Association, Vol. 78, No. 4, Dec. (2008). p. 999.

9. Ibid., p. 996.

10. Ibid., p. 997.

11. Ibid., p. 998.

12. Lee, Carol D. “Profile of an Independent Black Institution: African-Centered Education at Work.” Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 61, No.2, African Americans and Independent Schools: Status, Attainment and Issues, Spring 1992. pp. 160–177.

13. Ibid., pp. 167–168.

14. Ibid.

|