|

INDEPENDENCE DAY

(Honoring those who helped gain our independence)

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Sunday, July 5, 2009

Bernice Johnson Reagon, Lectionary Team Cultural Resource Commentator

I. Introduction

The Fourth of July, or Independence Day, the celebration of the birth of America, is generally observed as a civic and social occasion. On the civic level, there are parades with marching bands, floats, drill teams, armor guards, and outdoor concerts with the reading of the Declaration of Independence by local students and speeches from local leaders, occasionally including candidates running for office.

In the nation’s capital, on the National Mall, this day is the highest day of a national folk festival produced by the Smithsonian Institution. The Festival of American Folklife celebrates the United States of America as a nation of many cultures and peoples through its presentation of performances, crafts, and other cultural exhibits honoring the many who form the heart and breath of this land. As soon as it is dark, massive fireworks displays, visible for miles, light up the sky.

For families, the Fourth of July is often observed as a time for friends and family to come together for a day and evening of summertime outdoor fun: backyard barbecues, music and dances and, legal or not, fireworks. The Fourth of July weekend is also a time when many of our churches sponsor an outing in a local park with picnic tables loaded with food and games for young and old occasionally including a baseball game and other types of athletic activities by the members.

Our lectionary scripture for this Independence Day is Galatians 5:1-13. If I had to attach a theme to accompany this scripture and reflect the focus of this day on the calendar, it would be liberty. In the first verse of our scripture we find: “It is for freedom that Christ has set us free. ‘Stand firm’ then, and do not let yourself be burdened again by the yoke of slavery.” The text goes on to suggest that cultural bindings, or requirements observed or not observed, hold no weight in what really will bring true freedom, which is expressed as, “Faith expressing itself through love.” We are called to be free, but with freedom comes the call to move forward in love not in sin.

II. Etymology of Terms

Etymology of Liberty – From the old French (circa 1375), “liberté” means “freedom;” from the Latin “libertatem” we get “freedom, condition of a freeman;” also from Latin, “liber” means “free.” “To take liberties” means “go beyond the bounds of propriety” (1625). The “sense of ‘privileges’ led to the sense of ‘a person’s private land’ (1455), which yielded” to a sense of place in eighteenth century England and in America of “‘a district within a county but having its own justice of the peace,’ and also ‘a district adjacent to a city and in some degree under its municipal jurisdiction’” (for example, the Northern Liberties of Philadelphia would operate under the jurisdiction of Philadelphia).1

The very concept of “liberty” has often been partnered with the concept of “boundaries” or “ownership.” There can be, from different or opposing positions, the need to “be free” or “be at liberty” by one. But, it may be the opinion of another that the one taking that position is in violation of another who considers it against his or her claims as it relates that particular life, property, labor and production.

Within the African America community, these concepts are crucial because we are a people who, over several centuries, were brought by force to these shores with our liberties taken from us by others. The spirit within us, even as we labored to build this county, kept alive our core that knew that slavery was not right. Thus, our culture constantly places in front of us the idea of taking a “leave of absence” from boundaries placed upon us to claim for our own selves our own territorial application of justice in search of peace.

Etymology of Independence and Dependent – “Subject” (1382) means to make a person or nation “‘subject to another by force,’ also ‘to render submissive or dependent;’” from the Latin “subjectare” (1549) “meaning ‘to lay open or expose (to some force or occurrence).’”2 From 1600, the French, “independent,” means “not dependent.”3 “Dependent,” from 1607, is from “rely,” “reliance,” or the adjective “reliant.” There is a relationship between “dependent,” “reliance” and “precarious.”4 In 1646, “precarious” is a legal word meaning “held through the favor of another;” from Latin “precarius” means “obtained by asking or praying;” “from prex (gen. precis) ‘entreaty, prayer.’” “Notion of ‘dependent on the will of another’ led to sense ‘risky, dangerous, uncertain’ (1687).” In 1791, U.S. Independence Day (July 4) was first recorded under that name.5

Etymology of Bondage – In 1303, “bondage” is the “condition of a serf or slave,” evolved from Anglo-Latin bondagium, from Middle English, “bond ‘a serf, tenant farmer,’ from Old English, bonda ‘householder,’ from O.N. bondi, from boandi ‘free-born farmer,’ lit. proposition form of boa ‘dwell, prepare, inhabit.’ Meaning in English changed by influence of bond.”6

III. Historical Documents

Most civil or cultural celebrations of Independence Day are observed on the date the Declaration of Independence was signed by Congress, July 4, 1776. It is important to note that declaring one’s intention to break free from restrictions and boundaries does not in itself mean freedom. In the case of this Declaration, the colonies expressed their intention to break their relationship with England, England refused, and the War of Independence was the result. England’s loss and the victory of the Americans resulted in the establishment of a new independent nation.

The original draft of the Declaration was written by Thomas Jefferson and the final version revised and signed by members of the convening Congress. The Declaration stands as one of the most progressive statements of eighteenth century thinking. Its central theme is liberty, declaring the right to break from an unjust relationship; it itemized the abuses by England and the King and declared the Americans’ right and intention to break free from their colonial ownership status. The document’s creators grounded their positions in natural law, expressed as the “laws of nation,” and as an entitlement from the God of their understanding, expressed as “Nature’s God.”

The Final Version

The Declaration of Independence

IN CONGRESS, July 4, 1776

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America,

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, --

That whenever any form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed.

But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.--Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government.

The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good. He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.

He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only. He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures. He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people. He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative powers, incapable of annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within. He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands. He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary powers. He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries. He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people, and eat out their substance. He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures. He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power.

He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation: For Quartering large bodies of armed troops among us: For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the inhabitants of these States: For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world: For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent: For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury: For transporting us beyond seas to be tried for pretended offences: For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an arbitrary government, and enlarging its boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies: For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the forms of our Governments: For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.

He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us. He has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people. He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of cruelty & perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation. He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken captive on the high seas to bear arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands. He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince, whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Nor have we been wanting in attentions to our British brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the United States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, that these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.7

IV. Deletions from the Original Draft

Jefferson’s “original rough draft” of the Declaration of Independence included a reference to slavery as a result of British oppression. This was deleted from the final version, because several colony representatives determined that it would suggest that they

believed slavery was wrong in all instances and the world now knows that was not the case. The deleted material read as follows:

He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life & liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. This piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the CHRISTIAN king of Great Britain. determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought & sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or to restrain this execrable commerce: and that this assemblage of horrors might want no fact of distinguished die, he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he has deprived them, & murdering the people upon whom he also obtruded them; thus paying off former crimes committed against the liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.8

For a detailed analysis of the revisions to the Jefferson draft see the commentary of D. J. Mason.9

V. On Liberty

“Liberty” can be defined as going beyond prescribed boundaries. Independence Day, July 4, is celebrated not when Americans gained freedom from Britain, but when we proclaimed it. We declared that we were no longer of the British community, and Britain said no you are not leaving. The war was Britain’s refusal to accept our declaration to end of the relationship. The lesson: Once we declare ourselves independent, we have to be prepared to back it up.

Text from a Spiritual:

Never turn back, while I run this race

Never turn back, while I run this race

Never turn back, while I run this race

For I don’t want to run this race in vain.

African Americans have, from our arrival to these shores, before the Declaration of Independence, petitioned whatever governing structures that existed for a redress of grievances endured. After the Declaration of Independence, in these petitions we sometimes used the language of that Declaration of Independence to point to the extreme contradiction white Americans showed by holding Africans as slaves as these same white Americans struggled to be free of bondage from a colonial power.

I’m running running running Lord

I can’t tarry

I’m running on home to see the Lord

I got my ticket in my hand…

I got a message for the world…10

VI. Blacks Made Their Declarations of Independence, Too

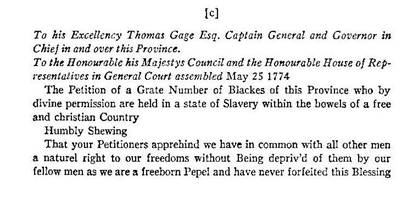

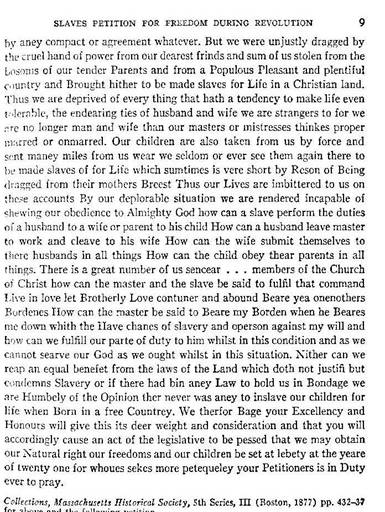

A. Petitions Against Slavery

Before and during the Revolutionary War, Negroes, both collectively and individually, made petitions and public pleas against slavery. They often pointed out the hypocrisies of the “so-called Christians” who were shouting “Liberty or Death.” A Massachusetts group of Negroes used Bible verses to contradict the behavior of the very people who used it to condemn them. They vividly explained how it was impossible to be compliant with Bible teaching while being held in slavery:

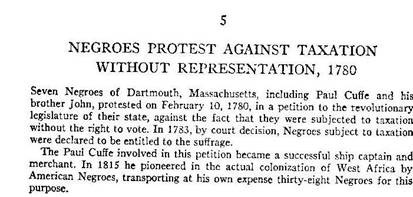

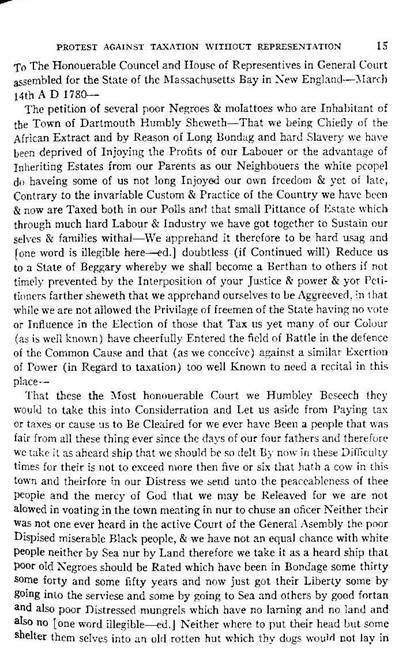

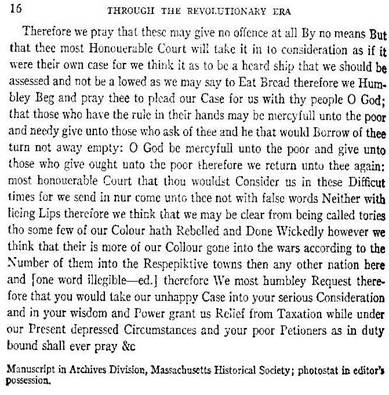

B. More Declarations

In 1780, seven Negroes from Dartmouth, Massachusetts protested against the fact that they were subjected to taxation without the right to vote. Among these petitioners were two brothers, Paul and John Cuffe. Paul became a successful ship captain and merchant. In 1815, at his own expense, he pioneered the colonization of West Africa by American Negroes. The petition vividly depicts the unjust and deplorable conditions that they (free people of color) were subject to, but they were nonetheless expected to pay taxes on the very little they had acquired. The petition also notes that, from their race, many have joined the fight for independence. The petition ends with a prayer and plea to God to come to the aid of the people of African descent and end this practice of taxation without representation. In 1783, by court decision, Negroes subject to taxation were declared to be entitled to vote.

C. Harriet Tubman and Her Declaration of Independence

Liberty for the colonies intensified the idea of liberty from slavery. During the nineteenth century, as the Moses of her people, Harriet Tubman would say, echoing Patrick Henry, “Give me liberty or death…” In the case of Tubman, gaining her freedom was not enough

“So it was with me,” she said. “I had crossed the line. I was free; but there was no one to welcome me to the land of freedom. I was a stranger in a strange land; and my home, after all, was down in Maryland; because my father, my mother, my brothers, and sisters, and friends were there. But I was free, and they should be free. I would make a home in the North and bring them there, God helping me. Oh, how I prayed then,” she said; “I said to de Lord, ‘I’m gwine to hole stiddy on to you, an’ I know you’ll see me through.’”11

Tis the old Ship of Zion

Tis the old ship of Zion

Tis the old ship of Zion

Get on board, get on board.

In a work commissioned for the opening of the National Center for the Underground Railroad, I opened with a selection based on the text from the nineteenth century warrior, Harriet Tubman. Here, Tubman defines liberty as a state to be desired and reached for beyond protecting the state of being “alive.”

For I had reasoned this out in my mind,

There was one of two things I had a right to

Liberty or death

If I could not have one I would have the other,

Liberty or death,

There was one of two things I had a right to.12

This quality and understanding might also be the key lesson we try to share as we come together in the shadow of the national observance of Independence Day.

VII. Conclusion

Howard Thurman wrote:

Once when I was very young, my grandmother, sensing the meaning of the constant threat under which I was living, told me about the message of one of the slave ministers on her plantation. “You are not slaves; you are not ‘niggers’ condemned forever to do your master’s will, you are God’s children.” When those words were uttered a warm glow crept all through the very being of the slaves, and they felt the feeling of themselves run through them. Even at this far distance I can relive the pulsing tremor of raw energy that was released in me as I responded to her words. The sense of being permanently grounded in God gave to the people of that far off time a way to experience themselves as human beings.13

Thurman believed that this was just one part. Not only should the person experience oneself as a human being, but the community of believers must also be involved in this kind of experience.14

For the African American church, Independence Day is an important opportunity to explore the meaning of “liberty,” “freedom,” and “independence” in civic, social and spiritual life. In this lesson, we are invited to consider the idea of bondage, the meaning of belonging to someone else against one’s intent or will, the need to be free as a person, as a member of a community, as a member of the church; as one who carries within their being the legacy of overcoming slavery in the United States of America while often at the same time operating to support, protect and defend this nation of our birth.

Contemporary discussions about what it means to be free could be a teaching moment within all age groups. When I read Paul’s words about the meaning of being “free” as followers of the Christ, I am comforted.

Notes

1. “Liberty.” Online Etymology Dictionary. 2001. Online location: http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=liberty&searchmode=none accessed 5 February 2009

2. “Subject.” Online Etymology Dictionary. 2001. Online location: http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=subject&searchmode=none accessed 5 February 2009

3. “Independent.” Online Etymology Dictionary. 2001. Online location: http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=independent&searchmode=none accessed 5 February 2009

4. “Dependent.” Online Etymology Dictionary. 2001. Online location:

http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=dependent accessed 5 February 2009

5. “Precarious.” Online Etymology Dictionary. 2001. Online location: http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=precarious&searchmode=none accessed 5 February 2009

6. “Bondage.” Online Etymology Dictionary. Online location: http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=bondage&searchmode=none accessed 5 February 2009

7. United States. US National Archives & Records Administration. The Declaration of Independence: A Transcription. Online location: http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/print_friendly.html?page=declaration_transcript_content.html&title=NARA%20%7C%20The%20Declaration%20of%20Independence%3A%20A%20Transcription accessed 5 February 2009

8. United States. Library of Congress. Declaring Independence: Drafting the Documents. Online location: http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/declara/ruffdrft.html accessed 5 February 2009

9. “The Hypertext Declaration of Independence.” Duke University. Online location: http://www.duke.edu/eng169s2/group1/lex3/hyprdecl.htm; and D.J. Mason’s commentaries online location: The Declaration of Independence homepage. http://web.duke.edu/eng169s2/group1/lex3/firstpge.htm accessed 5 February 2009

10. “While I Run this Race.” Negro Spiritual

11. Aptheker, Herbert. A Documentary History of the Negro People in the United States. 1951. New York, NY: Carol Pub. Group, 1990.

12. Bradford, Sarah H. Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman. The Black Heritage Library Collection. Freeport, NY.: Books for Libraries Press, 1971.

13. Johnson Reagon, Bernice. Liberty or Death Suite. Commissioned by Muse Women Choir, Cincinnati, Ohio, premiered June, 2004 in observance of the opening of the National Center for the Underground Railroad. Text fromBradford, Sarah H. Harriet Tubman: the Moses of Her People. 1869. Bedford, MA: Applewood Books, 1993.

14. Thurman, Howard. The Luminous Darkness: a Personal Interpretation of the Anatomy of Segregation and the Ground of Hope. New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1965. pp 101-110; also available from Thurman, Howard. The Luminous Darkness: a Personal Interpretation of the Anatomy of Segregation and the Ground of Hope. Richmond, IN: Friends United Press, 1989.

15. Ibid., p. 102.

|