|

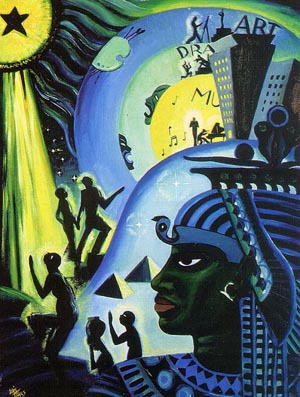

The Ascent of Ethiopia (1932)

by Lois Mailou Jones

AFRICAN HERITAGE SUNDAY

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Sunday, February 8, 2009

Juan Floyd-Thomas, Lectionary Team Cultural Resource Commentator

I. The History Section

Africa is a continent not a country.

Anonymous

Whatever you do, do not let them begin

your history with slavery; we did not begin there.

Asa Hillard III

In his 1829 publication, Ethiopian Manifesto, Robert Alexander Young identifies all members of the African diaspora as “Ethiopians.” Using this archaic form of address for all people of African descent, Young understands black women, men, and children as having a common heritage derived from Africa and referencing Psalm 68:31, which states, “Princes shall come out of Egypt; Ethiopia shall soon stretch out her hands to God.” In calling all conscious black people “Ethiopians,” Young claims a collective sense of identity for all black people in an early manifestation of Black Nationalism. As with many slave preachers and abolitionists of the antebellum era, Young understood African Americans—both enslaved and free—to be living in a wicked and sinful land much like ancient Egypt described in the Hebrew Bible. For black people during slavery, neither the identities of the sinners nor the saved needed much clarification. Because of this, Young argued that God would deliver his children to a state of grace in direct proportion to the suffering they had already endured.

Whether discussing Noah, Moses, or Jesus himself, Young’s emphasis of the divine messenger of God as an intercessor between the human and the divine appears with one primary purpose — to rescue God’s chosen people from a land doomed to its own destruction. In both historical and contemporary terms, African Americans can find a group identity linked to a cultural heritage rooted in African ancestry in ways that are both positive and affirming.

An Excerpt from the Ethiopian Manifesto (1829):

Ethiopians! open your minds to reason; let therein weigh the effects of truth, wisdom, and justice, (and a regard to your individual as general good,) and the spirit of these our words, we know full well, cannot but produce the effect for which they are by us here from intended. Know, then, in your present state or standing, in your sphere of government in any nation within which you reside, we hold and contend you enjoy but few of your rights of government within them. We here speak of the whole of the Ethiopian people, as we admit not even those in their state of native simplicity, to be in an enjoyment of their rights as bestowed to them of the great bequest of God to man.

The impositions practiced to their state, not being known to them from the heavy and darksome clouds of ignorance which so [woefully] obscures their reason, we do, therefore, for the recovering them, as well as establishing to you your rights, proclaim, that duty-imperious duty, exacts the convocation of ourselves in a body politic; that we do, for the promotion and welfare of our order, establish to ourselves a people framed unto the likeness of that order, which from our mind’s eye we do evidently discern governs the universal creation. Beholding but one sole power, supremacy, or head, we do of that head, but hope and look forward for succor in the accomplishment of the great design which he hath, in his wisdom, promoted us to its undertaking.

We find we possess in ourselves an understanding; of this we are taught to know the ends of right and wrong, that depression should come upon us or any of our race, of the wrongs inflicted on us of men. We know in our-selves we possess a right to see ourselves justified therefrom, of the right of God; knowing, but of his power hath he decreed to man, that either in himself he stands, or by himself he falls. Fallen, sadly, sadly low indeed, hath become our race, when we behold it reduced but to an enslaved state, to raise it from its degenerate sphere, and instill into it the rights of men, are the ends intended of these words; here we are met in ourselves, we constitute but one, aided, as we trust, by the effulgent light of wisdom to a discernment of the path which shall lead us to the collecting together of a people, rendered disobedient to the great dictates of nature, by the barbarity that hath been practised upon them from generation to generation, of the will of their more cruel fellow-men. Am I, because I am a descendant of a mixed race of men, whose shade hath stamped them with the hue of black, to deem myself less eligible to the attainment of the great gift allotted of God to man, than are any other of whatsoever cast you please, deemed from being white, as being more exalted than the black? ...

Beware! Know thyselves [slaveholders] to be but mortal men, doomed to the good or evil, as your works shall merit from you. Pride ye not yourselves in the greatness of your worldly standing, since all things are but moth when contrasted with the invisible spirit, which in yourself maintains within you your course of action: That within you will, to the presence of your God, be at all times your sole accuser.

Weigh well these my words in the balance of your [conscientious] reason, and abide the judgment thereof to your own standing, for we tell you of a surety, the decree hath already passed the judgment seat of an undeviating God, wherein he hath said, “surely hath the cries of the black, a most persecuted people, ascended to my throne and craved my mercy; now, behold! I will stretch forth mine hand and gather them to the palm, that they become unto me a people, and I unto them their God...

Peace and Liberty to the Ethiopian first, as also all other grades of men, is the invocation we offer to the throne of God.”1

II. A Song that Speaks to the Moment

“African” is the title of a song by the late reggae superstar Peter Tosh from his 1977 album Equal Rights. Lyrically, the song offers strong arguments regarding pan-Africanism in that Tosh argues that black people all over the world have an African identity. There are numerous references to Africa within Jamaican Christian and Rastafarian traditions, both in terms of biblical exegesis but also theological exposition of the nature of black women, men, and children living in exile from Africa their ancient homeland. Indicating ways in which, regardless of nationality, religious denominationalism, region, and internalized self-hatred, Tosh’s simple yet powerful song illustrates how important it is to focus on what unites us—a shared history, culture, and faith derived from the land of our ancestors—rather than any of the countless trivial things that divide us.

African

Don't care where you come from

As long as you're a black man

You're an African

Chorus

No mind your nationality

You have got the identity of an African

'Cause if you come from Clarendon

And if you come from Portland

And if you come from Westmoreland

You're an African

Chorus

No mind your nationality

You've got the identity of an African

'Cause if you come Trinidad

And if you come from Nassau

And if you come from Cuba

You're an African

Chorus

No mind your complexion

There is no rejection

You're an African

'Cause if your plexion

High(3x)

If your complexion low, low, low

And if your plexion in between

You're an African

CHORUS

No mind denomination

That is only segregation

You're an African

'Cause if you go to the Catholic

And if you go to the Methodist

And if you go to the Church of Gods

You're an African

CHORUS

No mind your nationality

You have got the identity of an African

'Cause if you come from Brixton

And if you come from Weesday

And if you come from Wingstead

And if you come from France

And if you come from Brooklyn

And if you come from Queens

And if you come from Manhattan

And if you come from Canada

And if you come from Miami

And if you come from Switzerland

And if you come from Germany

And if you come from Russia

And if you come from Taiwan.

III. Cultural Responses to Significant Aspects of Today’s Scripture

Historical Lesson

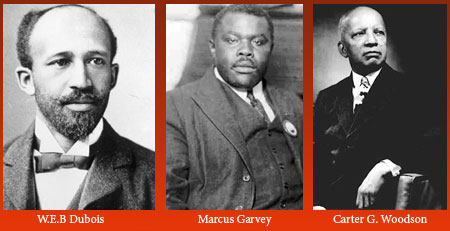

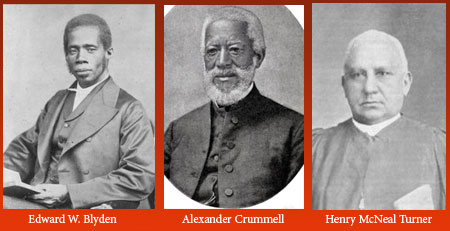

When considering the occasion of African Heritage Sunday, it is crucial to turn our attentions to why it originally came into existence. The concept of African Heritage Sunday is rooted in the pioneering scholarship and activism of black intellectuals and political figures such as Edward W. Blyden, W.E.B. Du Bois, J.A. Rogers, Marcus M. Garvey, George Padmore, and Carter G. Woodson during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century who sought to refute the collective falsehoods that African cultures and peoples contributed nothing of importance to world history and civilization. Likewise, the efforts of black religious leaders such as Alexander Crummell and Henry McNeal Turner made significant appeals amongst African Americans of the era to reconnect in meaningful ways with their African counterparts in the hopes of elevating the social and spiritual state of black people on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Such rethinking of Africa’s importance on the world historical stage, in both scholarly and spiritual terms, eventually led to some of the most robust artistic and political developments of the twentieth century, such as the Harlem Renaissance and Pan-Africanism respectively.

By the mid-twentieth century, the tremendous global transformations of the era gave rise to the rebirth of “Mother Africa.” With the creation of Ghana in 1957 as the first independent African nation, the world witnessed the emergence of Kwame Nkrumah not only as the first African elected president of a modern democratic society but also as a leader whose political philosophy was avowedly African-centered. From the moment his leadership of modern-day Ghana was declared, President Nkrumah was hailed by his nation’s citizenry as “Osagyefo,” an Akan word meaning “redeemer.” The impact of this awakening of African liberation from European imperialism was such an impressive event that several years later, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. would note the significance of the African independence movement on helping to inspire the nonviolent civil rights movement in the American South.2

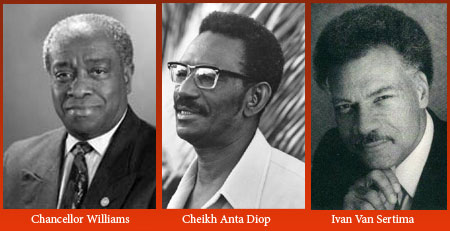

The social and political upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s created opportunities for African-centered scholars to challenge the dominance of Eurocentric ideas and perspectives within academic circles. Directly confronting generations of neglect, or outright denials of African presence and significance in world affairs, increasing amounts of research on Africa and the global community of African-descended peoples began to surface with a decidedly more African worldview. Works such as George James’ Stolen Legacy, Chancellor Williams’ The Destruction of Black Civilization, Cheikh Anta Diop’s The African Origins of Civilization: Myth or Reality, and Ivan Van Sertima’s They Came Before Columbus: The African Presence in Ancient America were among a handful of books that sparked a new consciousness about African racial identity. This revolutionary ideal eventually coalesced under the label of what subsequently became known as Afrocentrism in the late twentieth century.3

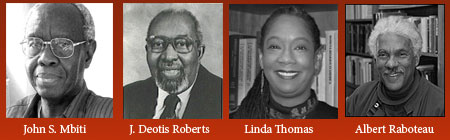

As important as this African-centered awakening has been in other aspects of African American life and culture, nowhere has it been more needed than in the realm of black religion and spirituality. As one of Africa’s foremost religious scholars, theologian John S. Mbiti’s book, African Religions and Philosophy, was one of the earliest works to significantly challenge dominant Western assumptions that traditional African religious ideas were “demonic and anti-Christian” in nature and, therefore, deserving of absolute contempt. Moreover, Mbiti’s groundbreaking work shattered preconceived and prejudiced assumptions about African religions and philosophy for an entire generation. In subsequent years, black religious scholars such as Albert Raboteau, Randall C. Bailey, Linda E. Thomas, J. Deotis Roberts, and Dianne Stewart, among others, have provided excellent theological resources that help bridge the gap between Africa and the Americas. Their research and writing represents the wide-ranging influences of African history, culture, and religion that bind all black people.

Thus, on the occasion of African Heritage Sunday, we get to acknowledge and celebrate the “God of Ethiopia”—as any number of our ancestors once called God the Father of Jesus Christ without fear or shame—as the God of all oppressed peoples worldwide. This revealed truth upholds the great prospect that all people of African descent — whether they live in Africa, Europe, the Caribbean, or the Americas — to redeem and ultimately reclaim a spiritual inheritance that belongs to all of God’s children. Thus, on the occasion of African Heritage Sunday, we get to acknowledge and celebrate the “God of Ethiopia”—as any number of our ancestors once called God the Father of Jesus Christ without fear or shame—as the God of all oppressed peoples worldwide. This revealed truth upholds the great prospect that all people of African descent — whether they live in Africa, Europe, the Caribbean, or the Americas — to redeem and ultimately reclaim a spiritual inheritance that belongs to all of God’s children.

IV. Stories and Illustrations

It is strange and yet exciting to discuss African Heritage Sunday in an allegedly “post-racial” American society. Although the outcome of the 2008 presidential election was a triumphant victory for Senator Barack Obama by every stretch of the imagination, his ascendancy to the highest office in the land indicates why we need to emphasize our African roots more clearly now than ever before. Let me explain. As a child growing up in northern New Jersey during the 1970s, there were so many mixed messages about blackness in general and being of African descent in particular. On the one hand, living just a stone’s throw from Newark, New Jersey or New York City, the beauty of the Black Power era was made visible and real for anyone who had eyes to see it. I would marvel at adults with their Afros and dashikis as symbols of racial pride and cultural awakening born of the transformations of that era. On the other hand, however, there was—and, unfortunately, still is—a great level of mis-education (to borrow the great historian Carter G. Woodson’s term) of black women, men, and children concerning Africa and Africans.

Recently, it made news that Governor Sarah Palin, the former Republican vice presidential candidate, thought that Africa was a country and not a continent. Aside from what that says about her, the deep fear and sadness is that her lack of awareness about Africa is actually mirrored throughout the African American community today.

Quite frankly, too many folks whose skins have been kissed by the glory of God’s sun know frighteningly little about their homeland and its ongoing legacy in the world. Aside from the continued neglect and underdevelopment of African history and culture within most educational curricula from kindergarten to college, we see the overwhelming ignorance of the Motherland and her children at play in both the mass media and popular culture. For example, whether on the nightly news or in televised humanitarian appeals by charitable faith-based organizations, the African continent is perpetually shown as the land of death, debt, disease, droughts, and dictators. Whereas those are sad realities, it must be stated that neither Africa nor Africans hold the monopoly on those cruel concerns of the human condition.

Moreover, such uninformed neglect serves as a paradox: African societies need help to overcome their economic suffering and political struggles, but we cannot help them until they begin to resolve their economic suffering and political struggles. As such, this becomes a horrible self-fulfilling prophecy of sorts. Another example lies in the recent trend of Hollywood celebrities adopting African orphans. Regardless of the various problems associated with this practice, it is significant that wealthy white musicians and movie stars have more awareness about the plight of African children than most African Americans do. There is great psychic and spiritual pain attached to the fact that there are still too many black people who still respond with tears, shrieks, and supreme indignation when they are identified as being of African descent.

Therefore, African Heritage Sunday is a vitally necessary corrective to general societal disregard of the African diaspora by emphasizing the overall importance of African people’s contributions in world culture, philosophy, history, and religion. We can take this opportunity to talk to one another about what is actually happening in African nations such as Senegal, Egypt, Sudan, Ghana, Somalia, Congo, Zimbabwe, and South Africa, among others, to dispel our functional ignorance about the continent which, in turn, leads us too often to being afraid and ashamed of our ancestral connections to Africa.

In light of all this, there is great and wonderful power at work in having a President of the United States who can not only trace his direct family lineage to Kenya but whose first name, Barack, is a Swahili term derived from the Arabic word meaning “blessing.” Even though he humbly referred to himself as “a skinny kid with a funny name” in his legendary speech at the 2004 Democratic National Convention, his meteoric rise from Ivy League-educated community organizer to the first U.S. president of African descent was made all the more profound by the fact that he did not try to hide or “Americanize” his name to appeal to racist voters who were turned off by the African roots made clear by his name.

V. Making It a Memorable Learning Moment

The following information is provided to assist preachers, Christian Educators, worship leaders, students, and community organizations in making African Heritage Sunday memorable.

- Beginning with the Ethiopian in today’s scripture, teach about African Biblical characters this Sunday and throughout the Year.

- For the sermonic moment:

In The Destruction of Black Civilization, Chancellor Williams writes:

The Blacks’ conception of God was on a scale too grand to be acceptable to Western minds. They had to reduce it by using a term that is equated with paganism, “primitive” backwardness and barbarism. The word is “animism.” But the historian and anthropologist are witnesses against themselves, still proving the very opposite of what they intend. In documenting animism as the chief characteristic of the religion of the Blacks from the remotest times, they are also documenting the fact that the Blacks’ belief in the existence, as well as the nature of one Universal God, also goes back to time immemorial.

And what is animism? As applied to Africans, it is the belief that the spirit of the Creator or the Universal God permeates all of His creations, living and dead. Therefore, any object, animate or inanimate, may be sacred. This concept of God and His creations would be regarded as highly “civilized” if expressed by a Westerner in some such terms as a “reverence for life.” Indeed, precisely the same African religious belief becomes the doctrine of “Immanence” in Christian civilization.

- The 1996 documentary, A Great and Mighty Walk, about Dr. John Henrik Clarke’s lifetime of Pan-African research, analysis, and activism, begins with his description of humankind’s initial move towards civilization in ancient Egypt. Dr. Clarke then moves effortlessly through a discussion of Africa’s other great empires, Mediterranean interactions during the Middle Ages, the Atlantic slave trade, European imperialism in Africa, the development of the Pan-African movement, and present-day African-American history. Functioning as both a biography of Clarke himself and an overview of the history of the African diaspora, the film offers provocative insights about human nature and world history from the perspective of a leading proponent of Afrocentrism.

- Africans in America, a six-hour PBS television series (with a companion website), chronicles the history of race and racism in the United States ranging from the beginning of the Atlantic slave trade to the end of the American Civil War. The series thoughtfully explores the central paradox that is at the heart of the American story: a democracy that declared all humans free and equal yet enslaved and oppressed one people in order to provide independence and prosperity to another.

- Hold a Book Fair – Make available books mentioned in this cultural resource unit, particularly:

- James, George G. M. Stolen Legacy: The Greeks Were Not the Authors of Greek Philosophy, But

the People of North Africa, Commonly Called the Egyptians. Trenton, NJ. Africa World Press, Inc.,

1992, 1954. This book can also be downloaded at no cost from various websites.

- Williams, Chancellor. The Destruction of Black Civilization: Great Issues of a Race from 4500 B.C.

to 2000 A.D. Chicago, IL: Third World Press, 1987.

- Diop, Cheikh Anta. The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality. New York, NY: L. Hill, 1974.

- Van Sertima, Ivan. They Came Before Columbus. New York, NY: Random House, 1976.

- Haley, Alex. Roots. Garden City, NY.: Doubleday, 1976.

- Felder, Cain Hope. Stony the Road We Trod: African American Biblical

Interpretation. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1991.

- Bailey, Randall C. and Jacquelyn Grant, Eds. The Recovery of Black

Presence: An Interdisciplinary Exploration. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1995.

- Roberts, J. Deotis. Africentric Christianity: A Theological Appraisal for

Ministry. Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press, 2000.

- Thomas, Linda E., Ed. Living Stones in the Household of God: The Legacy

and Future of Black Theology. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2003.

Notes

1. Young, Robert Alexander. “The Ethiopian Manifesto, Issued in Defence of the Blackman’s Rights, in the scale of Universal Freedom.” Ed. Herbert Aptheker. A Documentary History of the Negro People in the United States. Vol. 1, Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press, 1973. pp. 90-93.

2. King, Martin Luther. Why We Can't Wait. 1964. New York, NY: Signet Classic, 2000.

3. Asante, Molefi K. The Afrocentric Idea. 1987. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1998

|