|

ECONOMIC JUSTICE SUNDAY

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Sunday, February 28, 2010

Terrence L. Johnson, Guest Cultural Resource Commentator

Assistant Professor of Religion, Haverford College, Haverford, PA

I. A History Lesson That Can Reverberate

"The Montgomery Bus Boycott stands in the American imagination as the symbolic inauguration of the modern Civil Rights movement. Begun in 1955, the boycott crystallizes the overlap between religion and politics in late 20th century politics, demonstrating the useful role of black churches in particular in establishing the public character of black resistance against political and economic subjugation. For African Americans, long excluded from political institutions and denied presence, even relevance, in the dominant society’s myths about its heritage and national community, the church itself became the domain for the expression, celebration, and pursuit of a black collective will and identity.”1 Indeed, black churches, preachers and lay women served instrumental roles in triggering national and international attention on racial discrimination in the South.

The boycott’s philosophy included pulling resources from different segments of the community and organizing alternative modes of transportation for thousands of ordinary workers who felt the day-to-day burdens of the boycott as they walked miles to and from work. This expanded church teachings of life outside of worship. It also provides a clear template for us today if we want to change economic conditions in America. We who make up the Church must move beyond the Church walls and engage in action in the public square. We may not march; we may do internet campaigns instead; but, whatever the tools we use, economic justice requires that we step outside our comfort zones and our comfortable churches.

Also, something else that is overshadowed in reflections on this historic boycott, is the role of racial solidarity in defining black church responses to economic injustice. I am convinced that racial solidarity played an often overlooked role in the boycott. Why? Its philosophy of uplifting the masses established a collective will that demonstrated the strength of black power as an economic tool. Indeed, in response to white backlash against boycotters, many blacks began shopping only in black-owned businesses, which forced some white businesses to close.2 This played a role in establishing a belief in economic collectivism, a notion of ameliorating an unfair economy by establishing church-based credit unions, housing programs and job programs. This economic collectivism stands against a rugged individualism that is often reinforced within free market economies.

I wonder if black people have learned that economic collectivism would go a long way in combating the economic injustices that we still suffer in all arenas in America. What would it do for families and communities if we AGAIN opened our own stores, small or large; our own credit unions (Yes We Can open them); our own nail shops; our own car dealerships and our own cleaners? What would happen if blacks supported black dentists, gynecologists, lawyers, insurance agents, and black bankers? Do we understand the role of “us” in economic jUStice ?

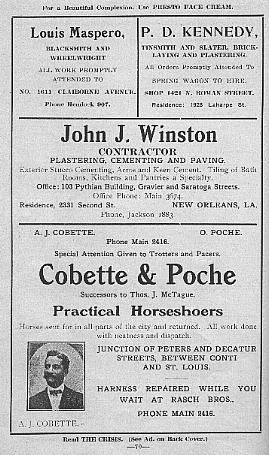

Sampling of Black Businesses in New Orleans in 1914

Perhaps more than any community in the late 1800s and early 1900s, blacks in Atlanta’s Auburn Avenue district (aka “Sweet Auburn”) were committed to economic justice for blacks and opened significant businesses. The following is a brief list of some of the financial institutions that were opened during this period. These institutions undergirded many of the black businesses that operated in Atlanta and provided financial assistance to churches through construction and renovation loans and loans to church members:

The Atlanta Loan and Trust Company was organized in 1891 by Wesley C. Redding and located at the corner of Bell and Auburn Street. It was chartered as a bank in 1916.

The Union Mutual Insurance Company set up headquarters in Atlanta in 1897 becoming the first chartered insurance association operated by African Americans in the state of Georgia.

The Atlanta Mutual Insurance company was formed in 1905 by Alonzo Herndon. Herndon began as a barber. By 1927, he was the wealthiest African American in Atlanta.

The Atlanta State Savings Bank was organized in 1913 and became the first chartered African American banking institution in Georgia.

In 1912 Herman Perry, an agent with Massachusetts Mutual Insurance Company, starts the Standard Life Insurance Company, the first legal reserve insurance company in the world operated by an African American.3

Sweet Auburn was greatly significant to black economic uplift. “Auburn Avenue was considered the almost nucleus so far as black businesses throughout America was concerned. It had more black financial institutions than any other city.”4 “Atlanta was a business Mecca. We had everything here that anybody just about had who was white. We had every kind of business, every kind of store, I’m talking about first class.5

Image of Atlanta Mutual Insurance Company (1975)

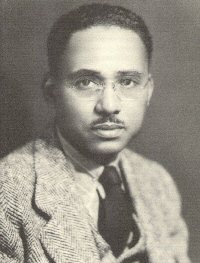

II. An Unheralded Advocate of African American Economic Uplift

Abram Lincoln Harris, Jr. was born in 1917 in Richmond, Virginia. His father was a butcher and his mother a school teacher. He graduated from Virginia Union University in 1922 with a Bachelor of Science and received an M.A. from the University of Pittsburgh in 1924. After teaching for a brief period at West Virginia State University, he became head of the Minneapolis Urban League. He wrote his Ph.D. thesis on the rift between African American and white labor in the United States. In 1930, he became the second African American to receive a doctorate in Economics in the United States. Abram Lincoln Harris, Jr. was born in 1917 in Richmond, Virginia. His father was a butcher and his mother a school teacher. He graduated from Virginia Union University in 1922 with a Bachelor of Science and received an M.A. from the University of Pittsburgh in 1924. After teaching for a brief period at West Virginia State University, he became head of the Minneapolis Urban League. He wrote his Ph.D. thesis on the rift between African American and white labor in the United States. In 1930, he became the second African American to receive a doctorate in Economics in the United States.

In 1931, he, along with political scientist Sterling Spero, produced a famous study of African American labor entitled The Black Worker, the Negro and the Labor Movement. Harris believed in a working-class political party and was against strategies such as the Garvey “Back to Africa Movement.” He called for such a party to be developed in a Progressive Labor Party pamphlet he published in 1930. His radical beliefs caused him to author a 1935 report titled The Harris Report in which he blasted the NAACP for not taking a more active and affirmative stance on race issues in the United Sates. He published his best known work in 1936, The Negro as Capitalist: A Study of the Great Depression. In this work, he argued that black businessmen had a false sense of racial solidarity with white businessmen but also strongly believed that unless black businesses participated in interracial their businesses would ultimately fail.

In 1937, he founded the liberal Social Science Division of Howard University and led the department through the early 1940s. He received the Guggenheim Fellowship for Economics in 1935, 1936, 1943 and 1953. In 1945, he moved to the University of Chicago and became one of the few African American academicians with a high ranking post at a white school. After joining this faculty, Harris did very little additional writing on economics and race. He died in November 1963. His writings on race and economics are still some of the most studied in America.6

III. Songs that Speak to the Moment

As African American churches reflect on the theological significance of economic justice, it is important to return to U.S. slavery as the starting point for individual and collective understanding of the role of capitalism in forming and fashioning black subjugation. The classic spiritual “Nor More Auction Block For Me” creates the cultural framework for contemplating the spiritual strength that the ancestors retrieved to define themselves as non-slaves and to create a vision of themselves as overcomers in a time of terror.

No More Auction Block For Me

No more auction block for me

No more, no more

No more auction block for me

Many thousand gone

No more peck of corn for me…

No more driver’s lash for me…

No more pint of salt for me…

No more hundred lash for me…

No more mistress’ call for me…7

The spiritual “Run Mary Run” reminds congregations that everyone stands within hand’s reach of achieving spiritual growth through the symbolic imagery of the tree of life. This imagery can be translated into a theological framework for building a broad economic vision for our people. The tree of life can be seen as a source that also contains the resources needed to build businesses and the necessary resources to create economic liberation. Although some historians have mistakenly considered songs such as this as “escapism songs,” our ancestors were wise enough to code songs that spoke of the other world with messages that were applicable to their freedom on earth. So, just as the enslaved knew that the other world was not like this, they also knew that this world should not be as it was, and their work to change it bears out this true belief.

Run Mary Run

Run, Mary, run

Run, Mary, run

Oh, run, Mary, run

I know de udder world is not like dis

Fire in de Eas’ an’ fire in de Wes’

I know de udder world is not like dis

Boun’ to burn de wilderness

I know de udder world is not like dis

Jordan river is a river to cross

I know de udder world is not like dis

Stretch yo’ rod an’ come across

I know de udder world is not like dis

Swing low, sweet chariot into de Eas’

I know de udder world is not like dis

Let God’s children have some peace

I know de udder world is not like dis

Swing low, sweet chariot in de Wes

I know de udder world is not like dis

Let God’s children have some res’

I know de udder world is not like dis

Swing low, sweet chariot in de Norf

I know de udder world is not like dis

Give me de gol’ widout de dross

I know de udder world is not like dis

Swing low, sweet chariot in de Sou’

I know de udder world is not like dis

Let God’s children sing and shout

I know de udder world is not like dis

If it was de judgment day

I know de udder world is not like dis

Ev’ry sinner would want to pray

I know de udder world is not like dis

Ol’ trouble it come like a gloomy cloud

I know de udder world is not like dis

Gadder thick an’ thunder loud

I know de udder world is not like dis.8

The contemporary song “Bless me” is the necessary model for promoting individual and collective prosperity during an economic downturn. The narrative in the song serves as a litany through which the individual and the Church collectively can petition God for their daily economic concerns. Our territory includes all that we need to live as healthy, happy and fulfilled African American Christians.

Bless Me (Prayer of Jabez)

Bless me, Bless me,

Oh Lord Bless me indeed

Enlarge my territory

Oh Lord Bless me indeed.9

IV. Stories and Illustrations

I am reminded of recently sitting across from my grandmother; I saw a flickering light in her eyes. In the light, I saw my grandmother kneeling in her garden.

My 83-year-old grandmother, Mary Kate Johnson, continues to grow okra, collards, cabbage and mustards in her backyard garden. Each morning she takes the hoe and softens the ground. Sometimes the garden is filled with chunks of dirt and rocks but, despite her old age, she simply hits the chunks until they soften. Her tired hands toil in the sun to create a bounty from tiny, ant-size seeds. Most of the garden’s content goes to unemployed neighbors or relatives. Even the cousin who seems to drink too much, the one who can never keep a job, is welcomed into her garden and at her table.

My grandmother is representative of nameless women who created from small amounts of resources the supply needed to care for their families. We will never possess all the narratives from which the ancestors cultivated their gardens. But their faith emerges through the churches, schools, major civic organizations and businesses they built. My grandmother’s garden reminds me of the tireless work involved in obtaining justice on all fronts.

We must create gardens (institutions, organizations and businesses that nurture the collective body). Our garden cannot grow if we hold it tightly and do not share it with others. When we hold tightly to our gardens we become cold and calloused, emotionally hardened; and a hardened heart is an awful thing to carry in this fragile body.

V. Audio Visual Aids and Books

Video Presentations for Economic Justice Sunday

Cross, June and Henry Louis Gates, et al. The Two Nations of Black America. Alexandria, Va.: Distributed by PBS Home Video, 2008.

Gilbert, Charlene. Homecoming- Sometimes I Am Haunted by Memories of Red Dirt and Clay. San Francisco, CA: [Distributed by] California Newsreel, 1998. Online location: http://www.pbs.org/itvs/homecoming/film1.html

Geary, Sean P., Mark Montgomery, and David Ackroyd. The Night Tulsa Burned. New York, NY: History Channel, 2002. Online location: http://www.history.com/classroom/admin/study_guide/archives/thc_guide.0317.html

Books

Marable, Manning. How Capitalism Underdeveloped Black America: Problems in Race, Political Economy, and Society. South End Press Classics, v. 4. Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2000.

Davis, Angela Y. Women, Race, & Class. New York, NY: Random House, 1981.

West, Cornel. Prophesy Deliverance!: An Afro-American Revolutionary Christianity. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1982.

Notes

1. Higginbotham, Evelyn Brooks. Righteous Discontent: The Women's Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880-1920. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993. p. 9.

2. Northrup, Cynthia Clark. The American Economy: An Historical Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC–CLIO Incorporated, 2003. p. 188.

3. This information is from a thesis project presented by Frances Hamilton to The Georgia Institute of Technology School of Information Design and Technology in May of 2002 to fulfill the requirements of a masters degree. Online location: http://www.sweetauburn.us/intro.htm accessed 29 October 2009

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. “Abram Lincoln Harris, Jr. Biography.” Encyclopedia of World Biography. Detroit, MI: Thomson Gale, 2006. Online location: http://www.bookrags.com/biography/abram-lincoln-harris-jr/ accessed 29 October 2009

7. “No More Auction Block for Me.” Online location: www.negrospirituals.com accessed 29 October 2009; see also Pike, Gustavus D. The Jubilee Singers: And Their Campaign for Twenty Thousand Dollars. Boston, MA: Lee and Shepard, 1873.

8. “Run Mary Run.” Online location: www.negrospirituals.com accessed 29 October 2009

9. “Lord Bless Me (The Prayer of Jabez).” Donald Lawrence. Donald Lawrence Presents the Tri-City Singers, Finale - Act II. Brentwood, TN: EMI Gospel, 2006.

|