|

CHILDREN’S SUNDAY (STOPPING ABUSE AND NEGLECT)

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Sunday, January 17, 2010

Stephen C. Finley, Guest Cultural Resource Commentator

Assistant Professor, Louisiana State University, Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies

& Program in African and African American Studies, Baton Rouge, LA

I. Introduction

This service is dedicated to celebrating children and to stopping child abuse and neglect. Implied in the emphasis that The African American Lectionary has placed on this day is belief in the inherent value of children and their need to be protected against all forms of harm. African American children have suffered from an historically rooted susceptibility of being sold away from their families on auction blocks, the perpetualness of racial oppression, social service agencies that separate African American families through forcible removal of children and subsequent foster care and adoption placements at greater rates than other communities, and legal systems that make it difficult to re-unite such families.1 This is not to suggest that there are not African American parents and other adults who abuse children as the lectionary commentary notes. The point simply needs to be made that African American children have always been vulnerable to neglect and abuse in America from so many quarters.

C. Eric Lincoln and Lawrence Mamiya, authors of The Black Church in the African American Experience, historically locate numerous responses to the precarious circumstances of black children in the programs and ministries of black churches after the Civil War. They explain, for instance, “Although worship services were oriented toward the adult members, special Sunday services were set aside for the participation of children and children’s choirs on ‘Children’s Day,’ or ‘junior church’ occasions.”2 Inclusion of children’s Sundays as worship occasions then have historic precedence and continue as vital opportunities for the community to coalesce around its children and to develop concrete ways for ensuring their safety and healthy development.

II. Cultural Response

Also, according to Lincoln and Mamiya, the black family and the church have always “shared a tradition of special caring for young children.”3 They suggest that the vulnerability of the existence of African American children during the centuries of slavery as well as the multiple decades of oppression that followed have given African American communities a unique view of children that was not shared by American society at large.4 Because African American children were so vulnerable, African American communities developed systems of “fictive kinship,” an informal system of “adoption” in which children were seen as belonging to the community and to family beyond the immediate nuclear unit. As a result, even children who were born without the benefit of marriage between their parents were not shunned as they may have been in English and American traditions. Rather, they were embraced as members of the extended family.5 Children’s Sunday offers black churches an opportunity to re-connect with an honored tradition and to create relationships and networks that benefit African American children and the entire community.

We cannot give in to the modern tendency to ignore children in trouble and wait until it is too late to help them. As churches and individuals, we can at least work to buttress the efforts of groups such as the Children’s Defense Fund (CDF) which has, for more than thirty-five years, stood at the forefront of the fight to help abused and all children. CDF is headquartered in Washington, D.C., and has offices in several states around the country: California, Minnesota, New York, Louisiana, Ohio, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee and Texas. CDF programs operate in 24 states and the National Outreach staff also works on the ground and with partners in all 50 states. They can be found online at www.childrensdefense.org. The CDF motto, “Leave No Child Behind,” must become the war cry of the entire African American community. We must lead in saving our children from abuse and neglect. If you are not sure how or where to begin, the CDF has suggestions on its website and can steer you to efforts in your local community. Your local United Way office will also have list of organizations that are working to help stop abuse and neglect of children. III. The Case of Neglected and Abused Children

Neglected Children

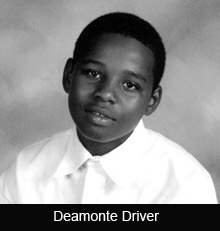

When you use the phrase neglected and abused children, most often people assume you are referring to a child who has been physically or mentally harmed by an adult caregiver. In the case of Deamonte Driver, he was neglected by the state government, the federal government and the American medical system. Neglect of children by federal and state entities is a common occurrence. It is likely to occur more frequently as states and the federal government continue to experience financial difficulties. In such circumstances, they will first cut services to those who are least able to advocate for them—including children. Deamonte Driver, died at the age of 12, in Prince George's County, Maryland. Deamonte was a seventh grader in Prince George's County, Maryland, just outside of Washington, D.C. He died because he couldn’t find a dentist who would accept Medicaid and his mother couldn't afford an $80 tooth extraction. The inexcusable loss of this 12-year-old's life started when he complained of a toothache. His mother, Alyce, who works at low-paying jobs, had been focused on finding a dentist to see Deamonte’s brother, who had six rotting teeth, when Deamonte began complaining of pain. When you use the phrase neglected and abused children, most often people assume you are referring to a child who has been physically or mentally harmed by an adult caregiver. In the case of Deamonte Driver, he was neglected by the state government, the federal government and the American medical system. Neglect of children by federal and state entities is a common occurrence. It is likely to occur more frequently as states and the federal government continue to experience financial difficulties. In such circumstances, they will first cut services to those who are least able to advocate for them—including children. Deamonte Driver, died at the age of 12, in Prince George's County, Maryland. Deamonte was a seventh grader in Prince George's County, Maryland, just outside of Washington, D.C. He died because he couldn’t find a dentist who would accept Medicaid and his mother couldn't afford an $80 tooth extraction. The inexcusable loss of this 12-year-old's life started when he complained of a toothache. His mother, Alyce, who works at low-paying jobs, had been focused on finding a dentist to see Deamonte’s brother, who had six rotting teeth, when Deamonte began complaining of pain.

After an unsuccessful search for a dentist who would accept Medicaid, Alyce took Deamonte to a hospital emergency room where he was given medicine for a headache, sinusitis and dental abscess and then sent home. But his condition soon took a turn for the worse, and he was back at the hospital being rushed to surgery where it was discovered that the bacteria from his abscessed tooth had spread to his brain. Heroic efforts were made to save him, including two operations and eight weeks of additional care and therapy, totaling about $250,000. Unfortunately, it was all too late. He died on February 25. The outrage is that Deamonte’s life could have been saved by a routine dental visit and an inexpensive extraction, if only Medicaid’s reimbursement rates to providers weren’t so low and the cost to see a dentist so high.6

Abused Children

The National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) reported an estimated 1,760 child fatalities in 2007. This translates to a rate of 2.35 children per 100,000 children in the general population. Many researchers and practitioners believe child fatalities due to abuse and neglect are underreported.

Research indicates that very young children (ages 3 and younger) are the most frequent victims of child fatalities. NCANDS data for 2007 demonstrated that children younger than 1 year accounted for 42.2 percent of fatalities, while children younger than 4 years accounted for more than three-quarters (75.7 percent) of fatalities. These children are the most vulnerable for many reasons, including their dependency, small size, and inability to defend themselves.7

How Do These Deaths Occur?

Fatal child abuse may involve repeated abuse over a period of time (e.g., battered child syndrome), or it may involve a single, impulsive incident (e.g., drowning, suffocating, or shaking a baby). In cases of fatal neglect, the child's death results not from anything the caregiver does, but from a caregiver's failure to act. The neglect may be chronic (e.g., extended malnourishment) or acute (e.g., an infant who drowns after being left unsupervised in the bathtub). “In 2007, slightly more than one-third of fatalities (35.2 percent) were caused by multiple forms of maltreatment. Neglect accounted for 34.1 percent and physical abuse for 26.4 percent. Medical neglect accounted for 1.2 percent of fatalities.” 8

Childhelp® is a national organization that provides crisis assistance and other counseling and referral services. The Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline is staffed 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, with professional crisis counselors who have access to a database of 55,000 emergency, social service, and support resources. All calls are anonymous. Contact them at 1.800.4.A.CHILD (1.800.422.4453).

If you suspect a child is being abused or neglected contact your local child protective services office or law enforcement agency, so professionals can assess the situation. Many States have a toll-free number to call to report suspected child abuse or neglect.

IV. Songs

In the touching selection, “What About the Children,” singer Yolanda Adams speaks of children who are broken hearted, whose dreams are choking and who are in need of love. She then raises a critical question for those of us who can help abused and neglected children: “If not for those who loved us, where would we be today?”

What About the Children

Tears streaming down, her heart is broken

Because her life is hurting, so am I

He wears a frown, his dreams are choking

And because he stands alone, his dreams will die

So, humbly I come to you and say

As I sound aloud the warfare of today

Hear me, I pray

What about the children?

To ignore is so easy

So many innocent children

Would choose the wrong way

So what about the children?

Remember when we were children?

And if not for those who loved us

And who cared enough to show us

Where would we be today?

Sir, where is your son? Where lies his refuge?

And if he can't come to you, then where can he run?

Such a foolish girl, yet still she's your daughter

And if you will just reminisce your days of young

You see, it's not where you've been

Nor what you've done because I know a friend

Who specializes in great outcomes

See his love overcomes

And what about the children?

To ignore is so easy

So many innocent children

Would choose the wrong way

Yes, what about the children?

Remember when we were children?

And if not for those who loved us

And who cared enough to show us

Where would we be today?

What about the children?

Don't just turn and walk away

What about the children?

They need our love and our help today

Yes, what about the children?

Remember when we were children?

And if not for those who loved us

And who cared enough to show us

Where would we be today?

Where would we be today?

Where would we be today?

What about the children?9

I selected the second and third song because they help children affirm what God believes about them—that they are all miracles and even at a young age should spread the love of God. Both allow for full-body participation when sung by children while teaching them important, affirming messages.

What A Miracle Am I

I have hands, I have hands,

Watch me clap, watch me clap.

Oh, what a miracle am I.

I have feet, I have feet,

Watch me stamp, watch me stamp.

Oh, what a miracle am I.

Chorus:

Oh, what a miracle, oh, what a miracle,

Every little part of me.

I'm something special, so very special,

There's nobody quite like me.

I have arms, I have arms,

Watch me swing, watch me swing.

Oh, what a miracle am I.

I have legs, I have legs,

They can bend and stretch, they can bend and stretch.

Oh, what a miracle am I.

(Repeat Chorus)

I have a spine, I have a spine,

It can twist and bend, it can twist and bend.

Oh, what a miracle am I.

I have one foot, I have one foot,

Watch me balance, watch me balance.

Oh, what a miracle am I.

(Repeat Chorus)10

Clap de Hands

Clap de hands

Stamp de feet

Spread the love of Jesus to everyone you meet

Ohhhh, clap de hands

Stomp de feet

Spread a little love around

Clap de hands

Stamp de feet

Spread the love of Jesus to everyone you meet

Ohhhh, clap de hands

Stomp de feet

Spread a little love around

The love of Jesus is a sweet, sweet song

That you can give to others as you walk along

A smile on your face and love in your heart

You spread the love of Jesus now everybody start

Clap de hands

Stamp de feet

Spread the love of Jesus to everyone you meet

Ohhhh, clap de hands

Stomp de feet

Spread a little love around

The love of Jesus is a miracle

God has given every boy and girl

He come down to earth because he loved us so

And now it's up to us to let his miracle show

Clap de hands

Stamp de feet

Spread the love of Jesus to everyone you meet

Ohhhh, clap de hands

Stomp de feet

Spread a little love around

Clap de hands

Stamp de feet

Spread the love of Jesus to everyone you meet

Ohhhh, clap de hands

Stomp de feet

Spread a little love around

Clap de hands

Stamp de feet

Spread the love of Jesus to everyone you meet

Ohhhh, clap de hands

Stomp de feet

Spread a little love around.11

The final song, “The Power of One,” is a riveting song that joins with the commentary and the cultural resource unit in asking each ONE of us to take personal responsibility for safeguarding children. We are reminded that ONE person has always made and can always make a difference.

The Power of One

One hand.

One heart.

One voice in the night.

One dream.

One song.

One chance to make it right.

This is the power of One

To do what must be done.

To stand for what you believe

Even though you are afraid

A difference is made,

A life is saved

With

One hand.

One heart.

One voice in the night.

One dream.

One song.

One chance to make it right.

This is the power you hold;

The truth must be told.

You are the rolling stone

That makes the mountain slide.

Your Spirit is tried.

You live with Pride, with

One hand.

One heart.

One voice in the night.

One dream.

One song.

One chance to make it right.

This is the power you are.

You must follow your star.

You alone hold the key

To your destiny.

With you it can be done.

You have the power of

One hand.

One heart.

One voice in the night.

One dream.

One song.

One chance to make it right.

One.11

V. Resources

Books

- Lincoln, C. Eric and Mamiya, Lawrence. “In My Mother’s House: The Black Church and Young People.” The Black Church in the African American Experience.

Durham, NC and London, UK: Duke University Press, 1990. pp. 309-45.

Websites

Notes

1. See, Dorothy E. Roberts. Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty. New York: Pantheon Books, 1997.

2. Lincoln, C. Eric and Lawrence Mamiya. The Black Church in the African American Experience. Durham, NC and London, UK: Duke University Press, 1990. pp. 311-2.

3. Ibid., p. 312.

4. Ibid., p. 310.

5. Ibid., p. 311.

6. This story was taken from the Children’s Defense Fund website. Online location: www.childrensdefense.org accessed 18 September 2009

7. The National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System

8. Ibid.

9. “What about the Children.” Written by Bebe Winans

10. “What a Miracle Am I.” Written by Hap Palmer

11. “One.” Written by Kat Gibson

|