|

CULTURAL RESOURCES

Friday, January 1, 2010

Anthony B. Pinn, Lectionary Team Cultural Resource Commentator

Lection - Daniel 6:23b (New Revised Standard Version)

I. Historical Considerations

For centuries, life in North America involved struggle, pain and despair with only glimmers of hope for millions of African Americans. This was the structure of life during the long dark days of slavery. Brought to this portion of the world to serve as free labor in the production of a nation within a framework of white supremacy, enslaved Africans and their descendents saw little historical reason to believe this situation would change in any significant way. Racism was strong, and the desire to maintain the structures of the slave system even stronger. A select few were able to buy their freedom, and walked to freedom under the cover of night with the help of a few good people. But the vast majority encountered the damage of enslavement day after day. Yet, in spite of what appeared to be a hopeless situation, many enslaved Africans maintained a determination that the situation would change, if not for themselves then for their children.

As the spirituals and slave narratives tell us, enslaved Africans in North America maintained their hopefulness because of a steadfast trust in the righteousness and goodwill of powers bigger than that of slaveholders and the government supporting the dehumanizing effects of enslavement. Humans were meant for freedom, and they knew freedom would eventually come their way. Drawing on the strength made available through biblical figures who faced similar circumstances (figures like Daniel waiting on the workings of God), they would eventually obtain their deliverance and their freedom.

For enslaved Africans in North America, this trust and the hard work they performed to maintain their dignity and to do what they could to gain greater liberty would be rewarded. They saw early signs of this through the potential for change in the midst of regional friction that would result in the Civil War. The fight over slavery would pull at the delicate connections between the northern and the southern states, and President Abraham Lincoln would gain the advantage for the North through the reluctant freeing of enslaved Africans.

The famous Emancipation Proclamation delivered by President Lincoln was delivered in two parts on September 22, 1862 and January 1, 1863. This was far from a smooth process, and there were clearly flaws in the mechanisms used to make real within reluctant states the requirements outlined in the Proclamation. As a consequence, some criticized the Proclamation for not going far enough on behalf of an oppressed community. Some time would pass before slaves in Texas, for example, received word that they had been freed. However, the Emancipation Proclamation did establish a mechanism by which to eventually gain the freedom of all enslaved Africans.

The Emancipation Proclamation and accompanying efforts provided a symbol of the promise of freedom which enslaved Africans and their descendents had trusted would occur. It was a clear sign for them that God was on the throne and all was well. In the claim to freedom made available to them, they saw the affirmation of their religious beliefs, and they marked their deliverance as an extension of God’s commitment to those that suffer and this coincided with the biblical stories of deliverance and salvation.

The freedom entailed in the Emancipation Proclamation would spark new ways of thinking about life and new approaches to the challenges of the political landscape of the United States. African Americans in large numbers took their freedom and began the movement to new locations to exercise freedom. We refer to this mass movement of African Americans during the period of the Civil War through the mid-twentieth century as the “Great Migration.”

II. Autobiographical Reflection

Circumstances can challenge the ability to maintain one’s trust in the inevitability of deliverance. Whether one thinks about deliverance as freedom from bad situations and circumstances within one’s personal life or liberation from troubled socio-political conditions affecting one’s community, time becomes a challenge. However deliverance is described or represented, it is a natural human reaction to wonder about timing: How long should it take for the forces of righteousness to intervene? What is the proper way to count the passage of time as one waits for substantive change to take place?

My grandmother would talk at length, and I enjoyed hearing the stories of her childhood and the challenges for her rather large family located in North Carolina. For my grandmother and grandfather, who knew of slavery through relatives who experienced it, the story of freedom and the new possibilities for African Americans urged them North. The time had come to forge a better life. My grandparents responded to the urge and made their way to Buffalo, New York. It was in Buffalo that they established themselves and reared their large family consistent with the promises and responsibility initially put in place through the thin but important workings of the Emancipation Proclamation.

My cousins and I grew up hearing the stories of this move North, the family left behind in North Carolina, and those distant relatives who first experienced freedom through President Lincoln’s proclamation. From these stories and the strength of my grandparents’ life and commitments, we learned the importance of trust and the ability to act based on how things should be and not be limited by current circumstances. I will always remember the words of my grandmother, a piece of wisdom she shared with me one day. “Walk through the world knowing your footsteps matter,” she said. In my grandmother and grandfather were signs that this careful and intentional movement through the world, this responsible approach to one’s impact on the world, can mean a great deal.

So long after the Emancipation Proclamation and decades after that initial freedom turned into the movement of a portion of my family North, the reasonableness of trust in new possibilities continues to mark the thinking and actions of many African Americans.

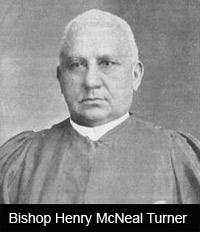

III. Biographical Reflection – Bishop Henry McNeal Turner

The African American Christian Tradition has marked the history of the United States in significant ways. So many leaders within that tradition have shaped the ways in which the United States understands and responds to the issues of race and racism highlighted during the Civil War, addressed through the Emancipation Proclamation, and felt during the rest of our history as a nation.

One of the most significant of these figures during the late nineteenth century and the early twentieth century was Bishop Henry McNeal Turner (1833-1915) of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. Although born free, Turner spent a significant amount of time working around enslaved Africans. As a result, he was well aware of the damage done to humanity through the brutality of enslavement. Turner well understood the sights and sounds of enslavement, but this reality did not prevent him from seeking the most out of life. Having taught himself to read and feeling a call to ministry, Turner was licensed to preach in 1853. He would eventually join the African Methodist Episcopal Church because of its “freedom” from white institutional structures. It would not take long for Turner to move through the ministerial ranks of the AME Church and become a bishop. His passion, insights, and determination to make a difference marked his approach to ministry and gained him the support of leaders and laity across the denomination.

What is so important about Turner is the way his feel for freedom and his trust in the eventual success of African Americans as a people were expressed through a theology that celebrated the beauty and value of black humanity. In 1895, he expressed this appreciation for African Americans in ways that connected them to God by proclaiming that God “Is a Negro!” Through a form of Black Nationalism, Turner spoke to the importance of African Americans for the welfare of the United States in spiritual as well as economic and political terms. He was convinced that African Americans represented in his historical moment the people whom God loved and set free. In this regard, the biblical Exodus event had significant meaning for him, as did the story of Daniel’s deliverance. For Turner, the promise of freedom first expressed through the Emancipation Proclamation had the will of God carved in it, and this spoke of God’s commitment to the welfare of African Americans.

IV. Songs That Speak to the Moment

Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel?

Any recognition of the Emancipation Proclamation and its meaning for so many generations of African Americans calls attention to the old and haunting spiritual, ”Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel? It draws directly from the biblical story of Daniel to explore and explain the changing historical circumstances of African Americans. Embedded in the lyrics is a commitment to trust in God and the expansive reach of righteousness.

Didn’t my Lord deliver Daniel

Deliver Daniel, deliver Daniel

Didn’t my Lord deliver Daniel

And why not-a every man.

He delivered Daniel from de lion’s den

Jonah from the belly of the whale

And the Hebrew children from the fiery furnace

And why not every man?

The moon run down in a purple stream

The sun forbear to shine

And every star disappear

King Jesus shall be mine

The wind blows east and the wind blows west

It blows like a judgement day

And every poor sinner that never did pray’ ll

Be glad to pray that day

Deliver Daniel, deliver Daniel

Didn’t my Lord deliver Daniel

And why not every man?

I see my foot on the Gospel ship

And the ship begin to sail

It landed me over on Canaan’s shore

And I’ll never come back no more

Can’t you see it’s coming

Can’t you see it’s coming

Can’t you see it’s coming…1

Trust and Obey

Gospel music, like the spirituals, expresses the tone and texture of the biblical witness. In this particular song, the importance of trust tied to the freedom and forward movement of African Americans noted above is urged in a passionate way. In fact, according to the lyrics of this song, it is only through obedience to the will of God, and trust in the workings of God’s intent through Christ that humanity can gain the richness of life so desperately desired.

When we walk with the Lord in the light of his Word,

What a glory he sheds on our way!

While we do his good will, he abides with us still,

And with all who will trust and obey.

Trust and obey, for there's no other way

To be happy in Jesus, but to trust and obey.

Not a shadow can rise, not a cloud in the skies,

But his smile quickly drives it away;

Not a doubt or a fear, not a sigh or a tear,

Can abide while we trust and obey.

Not a burden we bear, not a sorrow we share,

But our toil he doth richly repay;

Not a grief or a loss, not a frown or a cross,

But is blessed if we trust and obey.2

V. A Memorable Learning Moment

The date is June 18, 2009 and the event is somewhat noteworthy: the United States Senate apologizes for slavery that marked the character and practices of the United States for centuries. Surely this comes late, in that it is some one hundred and forty-six years after the Emancipation Proclamation. And, the statement offered by the Senate does not open for consideration the possibility of reparations. As the Washington Post reported:

The Senate's apology follows a similar apology passed last year by the

House. One key difference is that the Senate version explicitly deals with

the long-simmering issue of whether slavery descendants are entitled to

reparations, saying that the resolution cannot be used in support of

claims for restitution. The House is expected to revisit the issue next

week to conform its resolution to the Senate version.3

While failing to address the long lasting economic benefits of free labor for slaveholders and the financial hardship for enslaved Africans and their descendents, the apology that comes some time after several states apologized does speak to the historical weight of the evil and brutality African Americans encountered. It does amount to recognition of wrong done; and it speaks to what African Americans have known all along: African Americans are a people of substance whose presence in the United States matters and must be recognized. And, it speaks to the truth African American Christians assume when connecting themselves to the Old Testament figures delivered by God. This truth held tightly by African American Christians is simply expressed this way: trust in a righteous cause is more than justified!

VI. Learning More about this Moment

Video Presentations

Burns, Ken, Ric Burns, and David G. McCullough. The Civil War. (in 5 Discs). Burbank, CA: PBS Home Video, 2004.

Funk, Peter C. and John Irvin. The Civil War: The Anguish of Emancipation. 1972. Shaping of the American nation. St. Louis, MO: Phoenix Learning Group, 2007. Guelzo, Allen C. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2006.

Franklin, John Hope. The Emancipation Proclamation. Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, 1995.

Sernett, Milton. Bound for the Promised Land: African American Religion and the Great Migration. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997. Notes

1. “Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel?” Traditional. Online location: http://www.negrospirituals.com/news-song/didn_t_my_lord_delier_daniel.htm accessed 10 September 2009

2. “Trust and Obey.” Text by John H. Sammis

3. Thompson, Krissah. “Senate Backs Apology for Slavery.” Washington Post. 19 June 2009. Online location: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/06/18/AR2009061803877.html accessed 10 September 2009

|